Insomnia is common in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and is associated with mental health conditions as well as IBD activity

Article information

Abstract

Background/Aims

Insomnia is common in people with chronic medical conditions, such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and is readily treatable through cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia. This study aimed to describe the associations with insomnia in people with IBD and its relationship to IBD-related disability.

Methods

An online questionnaire was administered through 3 tertiary IBD centers, social media, and Crohn’s Colitis Australia. The questionnaire included the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI), a validated assessment of insomnia. Measures of anxiety, depression, physical activity, and disability were also included. IBD activity was assessed using validated patient reported scores. A multivariate model was constructed for clinically significant insomnia and ISI scores. Subpopulations of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis were considered.

Results

In a cohort of 670 respondents the median age was 41 years (range, 32–70 years), with the majority female (78.4%), the majority had Crohn’s disease (57.3%). Increasingly severe disability was associated with worse insomnia score. Clinically significant insomnia was associated with clinically active IBD, abdominal pain, anxiety, and depression, in a multivariate model. In an ulcerative colitis population, Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index components of general well-being and urgency were associated with worse ISI score in a model including depression and anxiety. In those with Crohn’s disease, the multivariate model included Harvey Bradshaw Index score in addition to depression and anxiety.

Conclusions

Insomnia is common in people with IBD and is associated with increased disability. Abdominal pain and mental health conditions should prompt consideration for screening for insomnia and referral for cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia.

INTRODUCTION

Sleep quality is of increased interest in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Abnormal sleep has been associated with several poor health incomes including cardiovascular disease [1] and all-cause mortality in some studies [2]. Meta-analyses have suggested that poor sleep is prevalent in those with IBD [3], and more common in those with clinically active IBD [4], worse than controls [5] and associated with mental health conditions [6,7] and worse quality of life [8,9]. Longitudinal studies have suggested that sleep disturbance is associated with fatigue [10], disease activity [11-13] and, in Crohn’s disease, the risk of hospitalization [14]. Insomnia is likely the most common sleep disorder in an IBD population with studies suggesting a prevalence up to 58% [8,15].

Chronic insomnia is common in those with chronic medical conditions [16-18]. This has been attributed to the effect of the symptoms associated with the disease and may exist as a symptom of the chronic medical condition itself [19]. Chronic pain is commonly seen in those with chronic insomnia with a prevalence of up to 40% [20,21]. Finally, chronic insomnia has been associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease [22,23] and poor outcomes such as increased hospitalisation [24] and work absenteeism [25].

Others have postulated that the symptoms of active IBD, such as nocturnal diarrhea and abdominal pain, may lead to sleep fragmentation and the development of conditioned insomnia [26]. This sleep pattern then persists following resolution of a flare and movement into an inactive IBD state. Irritable bowel syndrome-like symptoms in people with IBD may also be important with poor sleep prevalent in those with IBS [27]. Mental health conditions, such as depression and anxiety, commonly coexist with IBD and are also associated with insomnia [28].

The IBD and sleep literature has considered associations and predictors of poor sleep [13,29-34]. However there is only a single study considering IBD factors related to insomnia–noting the role of mental health conditions was not considered [15]. This study therefore aimed to explore whether there are specific disease or demographic factors associated with insomnia in an unselected IBD cohort in order to inform specific targets for an interventional study.

METHODS

An online questionnaire was made available to people with IBD via tertiary hospital patient email lists, private gastroenterology practice email lists and social media associated with a patient support organization. Individuals with a self-reported diagnosis of IBD over 18 years of age were invited to participate. Demographic data such as age and sex were recorded, along with IBD-related data including disease duration and previous surgery. Ethics approval for this study was obtained from the Southern Adelaide Human Research Ethics Committee (203.20) and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

The Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) is a self-reported questionnaire that been validated for assessment of insomnia, evaluating the response to treatment, and as an outcome measure for insomnia research [35-37]. The index consists of 7 items with a 5-point Likert scale used to rate each item. A score between 0 and 7 is considered to indicate the absence of insomnia, 8 to 14 subthreshold insomnia, 15 to 21 moderate insomnia, and over 21 denotes severe insomnia. Clinically significant insomnia is defined as an ISI score greater or equal to 10 as is commonly used in screening [35].

IBD disease activity was assessed using the Harvey Bradshaw Index (HBI) in the case of Crohn’s disease with HBI > 5 considered active disease [38]. The patient reported version of the HBI was utilized in the survey, although a decision was made to maintain the general well-being and abdominal pain score similar to the physician HBI rather than using a 10-point Likert scale [39]. The Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index (SCCAI) was used in the case of ulcerative colitis, an SCCAI > 5 was considered active disease [40]. The patient reported form of the SCCAI was utilized in the survey [41]. The use of a self-reported SCCAI has been previously validated with good agreement with physician reported SCCAI [42]. The abdominal pain subscore from HBI was utilized to form an abdominal pain dichotomous variable with an abdominal pain subscore of mild used as the cutoff value, with values above mild encoded as one (present), and values mild or below encoded as a zero (absent). The nocturnal diarrhea subscore from SCCAI was utilized to form a nocturnal diarrhea dichotomous variable with a nocturnal diarrhea subscore of above 1 encoded as a one (present), and scores 1 or less encoded as a zero (absent).

Physical activity was assessed using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire Short Form [43]. This allows the calculation of metabolic equivalent of task values over a 1-week period of walking, moderate and vigorous activity, along with sitting time.

Anxiety was assessed using the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-Item Scale [44] with a score over 10 used to indicate likely clinically significant anxiety. The Patient Health Questionnaire 9 was used to assess depression with a score over 15 used to indicate likely clinically significant depression [45].

Disability was assessed using the IBD-disability index self-report (IBD-DI-SR) version [46]. The IBD-DI-SR is a validated self-reported measure of disability in an IBD population. It was developed as a self-report form and a short form of the IBD-DI [47]. The IBD-DI is considered an important endpoint for clinical trials and in clinical practice.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Stata SE 16 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). Inadequate completion of score or index led to that result being discarded. For normally distributed variables mean and standard deviation were reported with comparisons made using the Student t-test. For non-normally distributed variables median, and interquartile range were reported, with comparisons made using the Mann-Whitney U test. For categorical data Pearson chi-square test was used or Fisher exact test when appropriate. One-way analysis of variance used with Tukey post-hoc test and adjusted for multiple comparisons as appropriate. A generalized linear model was also constructed for outcome of ISI score with univariate and multivariate regression performed with this optimized by the Bayesian information criterion. Logistic regression was performed for an outcome of clinically significant insomnia (ISI > 15). A multivariate logistic regression model was built for outcomes of clinically significant insomnia including demographic variables. This was model optimized by sequentially adding and removing variables to maximize the likelihood function. The margins command was used for post-estimation of probabilities. Regression was repeated for Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis subpopulations. Disease active scores (HBI and SCCAI) and their relationship to insomnia were examined using one-way analysis of variance used with Tukey post-hoc test and adjusted for multiple comparisons as appropriate.

RESULTS

There were 670 responses to the online questionnaire. Completion rate for the questionnaire was 90.5%. Median age was 41 years (range, 32–70 years), with most being female (78.4%), the majority had Crohn’s disease (57.3%). The mean disease duration was 11.9 ± 10.4 years, 30% had undergone surgery for IBD and around half were on biologics (50.5%) (Table 1). Clinically significant depression (Patient Health Questionnaire 9 > 15) was seen in 18%, and clinically significant anxiety (Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-Item Scale > 10) was seen in 29%.

The median ISI score was 13 (interquartile range, 8–17). Clinically significant insomnia (ISI > 10) was seen in 62% of the cohort and over a third of the cohort had at least moderate insomnia (Table 2). A one-way analysis of variance revealed differences in disability scores (IBD-DI-SR) between insomnia severity groups (F(3,619) = 20.99, P<0.001) (Table 2), with disability scores worsening with increasing severity of insomnia. Tukey post-hoc test showed significant differences between all groups except moderate and severe insomnia groups who had similar disability scores (Supplementary Table 1).

ISI Threshold Scores with Analysis of Variance Used to Demonstrate Significant Difference between Disability Scores between Groups (IBD-DI-SR)

Factors associated with an outcome of ISI score on univariate generalized linear regression included obesity, medications for sleep, opioids, current smoking status, clinically active IBD, abdominal pain, clinically significant anxiety, clinically significant depression, and methotrexate (Table 3). The parameters maintained in the optimized multivariate model included opioids, clinically active IBD, abdominal pain, clinically significant anxiety, clinically significant depression, and methotrexate. The highest coefficient was seen with clinically significant depression (3.80; 95% confidence interval, 2.68–4.93; P<0.001).

Generalized Linear Univariate and Multivariate Regressions for Insomnia Severity Index Score, Optimized by the Bayesian Information Criterion

Factors associated with an outcome of clinically significant insomnia on univariate logistic regression included clinically active IBD, abdominal pain, clinically significant anxiety, and clinically significant depression (Table 4). The parameters retained in the optimized multivariate model included clinically active IBD, abdominal pain, clinically significant anxiety, and clinically significant depression. The highest odds ratio was seen with clinically significant depression (odds ratio, 3.32; 95% confidence interval, 1.89–5.83; P<0.001). The area under the receiver operator curve for the logistic regression model was 0.72.

Clinically significant insomnia was seen in 62% of the cohort. Utilizing the multivariate model for clinically significant insomnia post-estimation probabilities were calculated (Table 5). Clinically significant depression resulted in the largest increase in the probability of clinically significant insomnia (23%).

Ulcerative Colitis Population: Generalized Linear Regression for Insomnia Severity Index Score Reporting Univariate and Multivariate Regressions Optimized by the Bayesian Information Criterion

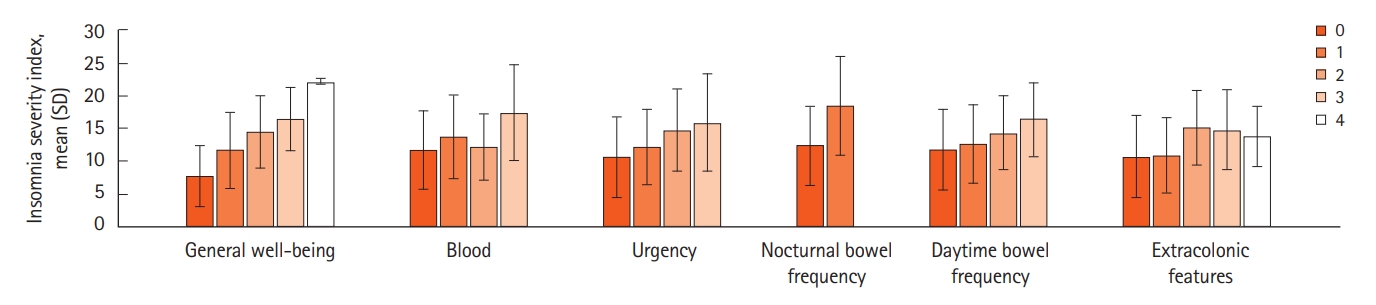

A subpopulation of ulcerative colitis was considered with all SCCAI score components significantly associated with ISI score (generalized linear regression) (Table 5). SCCAI general well-being and urgency score were included in an optimized multivariate model along with clinically significant anxiety, and clinically significant depression (Table 5). Despite abdominal pain not being part of the SCCAI this remained significantly associated with ISI score. Significant differences in mean ISI score were seen within all SCCAI component scores (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table 2). Increasing SCCAI component score was generally associated with increasing mean ISI score (Fig. 1), noting small patient numbers at the top end of SCCAI component scores. Frank blood was associated with a higher mean ISI score than no blood, with no further difference between the component scores seen.

Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index score component values and mean Insomnia Severity Index scores, with standard deviation as error bars. General well-being score varies from 0: very well, 1: slightly below par, 2: poor, 3: very poor, 4: terrible. Blood score varies from 0: none, 1: trace, 2: occasionally frank, 3: usually frank. Urgency score varies from 0: no urgency, 1: hurry, 2: immediately, 3: incontinence. Nocturnal bowel motions score varies from 0: 1–3 times, 1: 4–6 times. Daytime bowel motions score varies from 0: 1–3 times, 1: 4–6 times, 2: 7–9 times, 3: >9 times. The extracolonic features score is the number of active extracolonic features.

A subpopulation of Crohn’s disease was considered. An outcome of ISI score was significant for all HBI components, except for perianal disease and oral Crohn’s disease although this was limited by small numbers (Table 6). HBI score was included in a final optimized multivariate model, along with clinically significant anxiety, and clinically significant depression. Significant differences in mean HBI were seen within all HBI component (Fig. 2, Supplementary Table 3). Differences within HBI component score groups generally suggested higher HBI component score with higher mean ISI score (Fig. 2, Supplementary Table 3), once again limited by small numbers at the top end of HBI component scores.

Crohn’s Disease Population: Generalized Linear Regression for Insomnia Severity Index Score Reporting Univariate and Multivariate Regressions Optimized by the Bayesian Information Criterion

Harvey Bradshaw Index score component values and mean Insomnia Severity Index scores, with standard deviation as error bars. General well-being score varies from 0: very well, 1: slightly below par, 2: poor, 3: very poor, 4: terrible. Liquid stool per day score varies from 0: none, 1: once, 2: twice, 3: three or more liquid bowel actions a day. Abdominal pain score varies from 0: none, 1: mild, 2: moderate, 3: severe. The extraintestinal features score is the number of active extracolonic features.

DISCUSSION

In a large multicenter IBD cohort, insomnia was associated with each clinically active IBD, abdominal pain, depression, and anxiety. Insomnia was prevalent with clinically significant insomnia in over 60% of the cohort, with at least a third having moderate insomnia. The prevalence of insomnia reported in this cohort is similar to that reported in rheumatology populations [48] and similar to that reported in the other IBD cohort in the literature [15]. In the general population chronic insomnia rates range from 6% to 20% [49-51].

Insomnia has a well-established association with pain [21]. In our cohort, specifically, abdominal pain was associated with insomnia. The etiology of the abdominal pain, whether related to active inflammation or irritable bowel syndrome-like symptoms, was beyond the scope of this study. It is well established that sleep deprivation is associated with hyperalgesia [52] suggesting that insomnia if present may worsen any abdominal pain. Sleep disturbances have also been linked to other gastrointestinal symptoms such as diarrhea [53]. Nocturnal diarrhea was associated with insomnia in ulcerative colitis but not in Crohn’s disease. Data on other types of pain experienced by study participants was not available. Opioid usage, acting as an indicator of chronic pain, was associated with clinically significant insomnia and worse insomnia (higher ISI scores). SCCAI components urgency and general health were included in the final multivariate model for ISI score over the inclusion of the overall SCCAI score. This may be a result of the lack of differentiation the blood SCCAI component score provided between ISI scores. SCCAI and HBI component score general well-being may in part relate to the presence of any depression, anxiety, or disability.

Insomnia has been associated with mental health conditions [54,55]. Depression and anxiety were prevalent in this population and associated with insomnia. Sleep disruption is a common presentation of mood disorders [56]. Despite treatment of the underlying mood disorder residual symptoms persist which commonly will include insomnia [28]. Treatment for insomnia is widely available in the form of cognitive behavioral therapy targeted at insomnia (CBTi) [57,58]. There has been a pilot trial of CBTi in an IBD population where it was found to be feasible and acceptable [26]. The value of CBTi in those with mood disorders is unclear and treatment is typically first directed at the underlying mood disorder [59,60]. Similarly, pain should be controlled as possible noting the relationship between sleep and hyperalgesia and acknowledging that CBTi has shown some benefit in improving pain [61]. Limitations of this study include selection bias a result of the use of an online questionnaire that may attract people with sleep problems. Similarly, the form of survey and method of recruitment is likely responsible for the predominantly female cohort. Reporting bias may also be significant, noting a study of people with Crohn’s disease reported worse sleep quality than that observed by objective measures [6]. The absence of an objective measure of IBD activity is also considered a limitation. Further studies should consider objective measures of IBD activity and sleep quality. Studies incorporating mental health interventions in those with poor sleep should be pursued. The authors also acknowledge that there are many other factors the influence insomnia that were not measured in this study.

In conclusion, insomnia is common in people with IBD with at least a third having moderate insomnia and almost two-thirds meeting criteria which warrant insomnia screening. Insomnia is associated with increased disability, clinically active IBD and depression and anxiety. Mood disorders and abdominal pain may represent insomnia treatment targets in individuals with IBD prior to consideration of CBTi.

Notes

Funding Source

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of Interest

Andrews JM, Bryant RV, and Mountifield R received speakers fees and Ad Boards from Abbott, AbbVie, Allergan, Anatara, AstraZeneca, Bayer, BMS 2020, Celgene, Celltrion, Falk, Ferring, Gilead, Hospira, Immuninc, ImmunsanT, Janssen, MSD, Nestle, Novartis, Progenity, Pfizer, Sandoz, Shire, Takeda, Vifor, RAH Research Fund, The Hospital Research Fund 2020-2022, The Helmsley Trust 2020-2023. No other potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Author Contribution

Conceptualization: Barnes A, Andrews JM, Mukherjee S, Mountifield R. Data curation: Barnes A. Formal analysis: Barnes A. Methodology: Barnes A. Writing - original draft: Barnes A. Writing - review & editing: Barnes A, Andrews JM, Mukherjee S, Bryant RV, Bampton P, Fraser RJ. Approval of final manuscript: all authors.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary materials are available at the Intestinal Research website (https://www.irjournal.org).

Supplementary Table 1.

Tukey Post Hoc Test for Insomnia Severity Groupsa Defined by Insomnia Severity Index Scores and Disability Scores (IBD Disability Index Self-Report Questionnaire)

Supplementary Table 2.

Results of ANOVA Analysis of ISI from the SCCAI Components

Supplementary Table 3.

Results of ANOVA Analysis of ISI from the HBI Components