|

|

- Search

| Intest Res > Volume 20(1); 2022 > Article |

|

Abstract

Adults with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) search for self-management strategies to manage their symptoms and improve their quality of life (QOL). Physical activity (PA) is one of the self-management strategies widely adopted by adults with IBD. This integrative review aimed to synthesize the evidence on health outcomes of PA in adults with IBD as well as to identify the barriers to engaging in PA. Using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA), published literature was searched to identify the articles that addressed PA in adults with IBD. Twenty-eight articles met the inclusion criteria. Many of the reviewed studies used the terms of PA and exercise interchangeably. Walking was the most common PA reported in the studies. The findings from the majority of the reviewed studies supported the benefits of moderate-intensity exercise/PA among adults with IBD. The reviewed studies noted the following positive health outcomes of PA: improvement in QOL, mental health, sleep quality, gastrointestinal symptoms, fatigue and cardiorespiratory fitness. More importantly, participation in PA reduced the risk for development of IBD and the risk for future active disease. The findings from the reviewed studies highlighted the following barriers to engage in PA: fatigue, joint pain, abdominal pain, bowel urgency, active disease and depression.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic illness comprised of 2 forms of disorders: Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) [1]. The incidence rate of IBD is increasing worldwide, including developing countries where IBD was previously considered a rare disorder [2]. Adults with IBD present with many disturbing gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms, such as diarrhea, abdominal pain, bowel urgency, rectal bleeding, and extraintestinal manifestations [3]. Additionally, systemic symptoms, such as anxiety, depression, fatigue, sleep disturbances, and pain, are also common in adults with IBD [4]. The quality of life (QOL) of those with IBD is lowered due to the GI and systemic symptoms, as well as due to the extraintestinal manifestations [5,6]. Although, many advanced medical and surgical therapies are available to manage IBD, adults with IBD may look for other adjuvant options to manage their symptoms and improve their QOL. Physical activity (PA) is one such alternative intervention [7]. Exercise is an equivalent term used in the literature for PA, however it refers to more structured and repetitive activities [8].

Alterations in the intestinal immune system act as a trigger for IBD inflammation [9]. The anti-inflammatory benefits of exercise are well documented and are related to the control of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the intestinal system. In healthy individuals, the immune system of the intestine is in a state of equilibrium between pro- and anti-inflammatory mechanisms. However, disturbances in this equilibrium lead to the activation of the intestinal immune system and subsequent inflammation in IBD [9]. Animal model studies show that moderate exercise downregulates cytokines, such as interleukin-1 (IL-1) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, which reduce inflammation, suggesting a beneficial influence of exercise on IBD inflammation [9-11]. Additionally, the anti-inflammatory effects of exercise are related to the release of myokines from the muscles, such as IL-6, IL-10, and IL-1ra. These myokines inhibit TNF-α production, which reduces intestinal inflammation [10-12].

While reviews have been published on the benefits of PA for adults with IBD, reviews had mixed results and many reviews included older studies. Furthermore, many studies did not include barriers to engaging in PA/exercise among adults with IBD. Therefore, the aim of this review was to synthesize the literature on PA in adults with IBD with a focus on health outcomes of PA in adults with IBD as well as to identify the barriers to engage in PA by those with IBD.

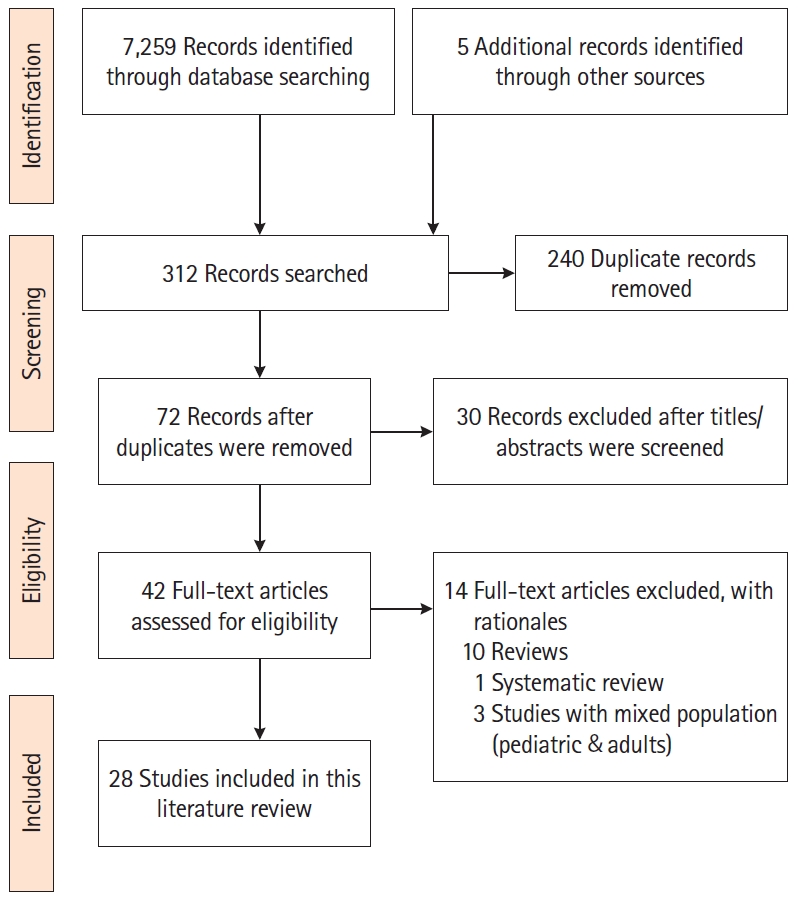

We conducted an integrative literature review from September 2019 to March 2020 to identify published articles that addressed PA/exercise in adults with IBD. The authors followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) as a framework to guide the literature search [13]. We searched the electronic databases of PubMed, CINAHL, Embase, Cochrane Controlled Trials Registry and Clinical Trials.Gov to identify the articles. The following keywords were used: “inflammatory bowel disease, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, physical activity, exercise, health outcomes, barriers, aerobic exercise, and resistance training.” The authors customized the keywords based on the requirements of each database. Additionally, the first author conducted a manual search of the selected studies to identify additional studies. The inclusion criteria of the studies were: (1) randomized and non-randomized studies, including cross-sectional studies that addressed exercise or PA; (2) studies published from 2007 to 2020; and (3) studies in English focused on adults (> 18 years) with IBD. The exclusion criteria were: (1) studies with pediatric population; (2) studies in other languages; and (3) reviews and conference abstracts. The PRISMA diagram (Fig. 1) illustrates the search process and the final selection of studies.

A total of 28 eligible studies were included for review. Of these, only 4 were randomized controlled trials; the rest were cross-sectional, prospective, descriptive, and case control studies. The study settings varied including Asia, Australia, Europe, and North America with a total sample of 8,168 adults. There were 15 studies with sample sizes of more than 100 [14-28]. For other details about the studies, including the author(s), year, study type, methods, and main findings, refer to Supplementary Table 1.

Although exercise is a subset of PA [8], many of the reviewed studies used these terms interchangeably. Twelve of the studies measured PA using self-report questionnaires. Of these studies, most used standardized tools, such as the Godin Leisure Time Questionnaire (GLTQ) [16,19,22,29] and the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) [27,28,30,31]. Various tools were used in the remaining studies. Details of PA measurement and characteristics were listed in Table 1.

Besides self-report, several researchers directly supervised the exercise activities of the participants. The supervised exercise activities were as follows: combined aerobic and resistance training under the supervision of a gym instructor [32]; a supervised running program [33]; progressive resistance training, which consisted of quadriceps training through leg extensions on a weight machine [26]; a cardiopulmonary exercise test [34]; evaluation of muscle strength (handgrip and quadriceps strength) using a dynamometer; the sit up test (ability to rise from a chair); and the gait speed test (walking velocity with a trainer) using a digital chronometer [35]. Additionally, high-intensity interval training (HIIT) and moderate-intensity continuous training (MICT) were also provided to adults with IBD using a leg cycle ergometer [36].

Other studies (n = 4) measured PA objectively but in an unsupervised manner. For example, one study measured a group of participants engaged in walking by having them wear pedometers [31]. In addition, 3 studies measured PA using accelerometers [37-39].

Exercise advice with the help of a PA trainer was also documented in the literature. For example, one study [40] focused on exercise advice as an intervention for adults with IBD. Each participant met with the researchers and a PA trainer for 15 minutes in week 1; advice was given to the participants on how to increase their PA by over 30% based on their personalized goals and instructions given to participants to track their PA goals and achievements in a diary [40].

The majority of the reviewed studies supported the benefits of systematic moderate-intensity exercise among adults with IBD [18,27,32-34]. However, 2 studies mentioned benefits from low-intensity physical activities [29,31]. In addition, a pilot study supported the feasibility and acceptability of high-intensity and moderate-intensity training [36]. In one study, the majority of the participants (52.9%) were engaged in high levels of PA [30]. The results of the other studies were inconclusive or did not measure the preferred intensity of PA due to their cross-sectional nature.

Walking was the most common type of PA reported [17,23,24,28,29,31]; followed by running [17,23,28,33]. Adults with IBD also participated in other physical activities, such as swimming, cycling, yoga, gardening/yardwork, home-based exercises, jogging, tennis, and gym exercise classes [23,24,28,29]. The exercise advice in one study recommended swimming, walking, and simple gym routines for less active individuals and active individuals were instructed to extend their activities, such as training for a 5-10 km run [40]. Two of the reviewed studies [26,36] provided resistance training to participants and one study offered a combination of aerobic and resistance training [32].

Adults with IBD reported improvements in their physical and mental health outcomes, as well as better management of IBD symptoms, after initiating exercise. Majority of the reviewed studies [25-27,30,32,33,36,37,39,40] measured QOL using Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire (IBDQ). This is a validated instrument to measure disease specific QOL among adults with IBD. In addition to IBDQ, 2 studies included EuroQOL to measure QOL [36,40], and 2 other studies measured QOL using Short Form 36 (SF-36) scale [27,37]. A direct positive relationship between QOL scores and exercise were reported in many studies; One study noted significant differences in the QOL scores between the exercise and non-exercise groups (P<0.05) [31]. Another study reported a positive correlation between QOL scores and PA which was measured using an accelerometer (P=0.03) [39]. Similar results were reported after progressive resistance training in 148 women with IBD; the QOL scores significantly improved (P=0.0001) after an 8-week training period [26]. Improved mean QOL scores was noted among participants who engaged in MICT [36]. Similar results were also observed among adults with CD, where physically active adults with CD reported greater QOL (P=0.022) [30]. In a cross-sectional survey, 79.4% of participants (n = 158) reported higher QOL after initiating exercise [19]. Meanwhile, the findings of another cross-sectional analysis revealed higher QOL with higher moderate to vigorous PA (> 150 min/wk; P<0.001) and increased walking (> 60 min/wk; P<0.01) [27]. Conversely, QOL scores did not differ between the exercise and control groups in a randomized control trial designed to measure the influence of a 10 week PA program in adults with IBD [33]. However, a significant improvement (P=0.023) in the QOL social subscores was noted, which suggested that exercise can promote QOL through improvements in social well-being [33]. Details of QOL results are summarized in Table 2.

PA influenced mental health outcomes and other IBD symptoms. Two studies noted that exercise led to improvements in mood [29,36]. Significant differences in stress scores between the exercise and control groups (P<0.05) were reported in one study with reduced stress scores among the participants of the exercise group [31]. Other additional benefits of PA included improved energy and sleep quality, fewer GI symptoms, and weight control [17,19,29,36].

Besides the improvement of physical, mental, and IBD symptoms, PA has been found to help reduce fatigue among adults with IBD. A longitudinal assessment of 86 adults with CD identified regular exercise as a modifiable behavior to reduce physical and cognitive fatigue among participants [41]. Fatigue scores were significantly lower in those who received exercise advice compared to those who received an exercise placebo (P=0.03) [40]. Another study tested 2 forms (HIIT and MICT) of exercise among adults with CD [36]. Fatigue scores were reduced in both groups, and the control group compared to baseline, but this did not differ among the groups.36 Two cross-sectional analyses found that higher levels of PA were associated with lower fatigue levels [14,15]. Specifically, participants who engaged in exercise for less than 30 minutes in a week experienced higher levels of fatigue (P=0.01) [14]. The summary of the results on fatigue are detailed in Table 3.

A few studies have reported the influence of PA on the cardiorespiratory fitness and body composition of adults with IBD. The cardiorespiratory fitness was measured using VO2 max (maximum oxygen uptake). Improved cardiorespiratory fitness (P=0.03) was observed among participants who engaged in moderate-intensity aerobic and resistance exercise programs for 8 weeks [32]. Participants of both HIIT, and MICT reported increased VO2 max after their sessions [36]. Interestingly, no statistically significant VO2 max results were noted between adults with active and inactive IBD [34]. Results of another study found significant changes in body composition parameters (reduction in percentage of total body fat, P=0.022 and increased lean tissue mass, P=0.003) among exercise program participants compared to the control group [32]; these results also support exercise as an inexpensive intervention to manage IBD-related sarcopenia and obesity-related metabolic disorders [32].

Many studies have highlighted the association between PA and the risk of developing IBD. The Nurse’s Health Study II data were evaluated to identify the association between exercise and the risk of developing IBD [23]. The PA data were collected every 2 to 4 years longitudinally in this cohort. PA was associated with a lower risk of developing CD [23]. The risk of developing CD reduced by 44% in women who did 9 hours of walking per week at an average pace. No association was noted between the risk of UC and PA [23]. The first population-based study of IBD risk factors in Asia-Pacific highlighted the protective effect of daily exercise in lowering the risk of developing CD in Asian adults with IBD [25]. Meanwhile, a Slovakian case control study reported that infrequent physical activities in childhood increased the risk of IBD [20]. In a longitudinal assessment, higher levels of exercise were significantly associated with reduced risk of active CD in adults with CD in remission (P=0.02) [22]. Additionally, 41.3% of adults with IBD (n = 158) in a cross-sectional survey (IBD diagnosed within the prior 18 months) reported that exercise helped to reduce their relapse rate [19]. Summary of the results are included in Table 4.

No definite conclusions of differences could be drawn on the health outcomes between supervised and unsupervised PA. For those studies which provided supervised PA [26,31-36,40], improvement in QOL was noted in some studies [26,31,33,36], reduced fatigue scores were noted in 2 studies [36,40], decreased total body fat, increased total lean tissue mass, and increased VO2 max in one of the studies [32]. No difference in exercise measurements were noted between participants with active IBD and inactive IBD in one supervised study [34]; and reduced lower limb performance and muscle strength were noted for adults with UC in another supervised study [35]. Similar findings were echoed in the reviewed studies which assessed PA without supervision. Improved QOL were observed in 2 of the studies [31-39]; no difference in QOL was noted in another study [37]; and lastly PA parameters were impaired among adults with CD [38].

Adults with IBD reported several barriers to engaging in PA. The most commonly reported barriers associated with lower PA/exercise were fatigue, joint pain, abdominal pain, bowel urgency, longer duration of disease, disease flare ups, and low vitamin D3 levels [17,18,28,38]. Depression and disease activity were negatively associated with PA in adults with CD (P<0.01), whereas depression and age were negatively associated with PA in adults with UC (P<0.01) [28]. In a study of 918 participants, 80% reported that they had to stop exercise for some period or permanently due to IBD diagnosis [17].

Analyses of the data from the research reports yielded mixed results regarding engagement in PA by adults with IBD. The results of 3 studies noted a lack of participation in exercise based on recommended guidelines [16,24,28]. Meanwhile, another study reported impaired PA parameters in adults with CD compared to healthy controls (P<0.01) [38]. Adults with CD preferred to spend their time carrying out light or sedentary activities as opposed to the recommended moderate to vigorous activity [38]. The findings of a more recent study highlighted that participants with CD and UC in remission tended to engage in higher levels of PA than those who had active disease, confirming active disease status as a barrier to engaging in PA [39]. In contrast, in another cross-sectional study, 85% of the participants with inactive IBD (n = 194) and 67% of the participants with active IBD (n = 118) were engaged in daily PA [21].

Five studies reported regular engagement in PA by more than half of the study participants [14,15,17,18,30]. The proportions of participation were: 64% (n = 182) [14], 86% (n = 113) [15], 66% (n = 918) [17], 57% (n = 17) [30], and 74% (n = 227) [18]. One cross-sectional study evaluated the physical fitness of adults with IBD in remission before and after diagnosis [19]. Adults diagnosed with IBD in the prior 18 months were included in the study. The majority of participants (69.5%, n = 158) reported that IBD diagnosis affected their PA level, whereas 30.5% did not report an effect. The diagnosis of IBD reduced participation in PA among individuals who were previously involved with sports. However, 44.3% of the participants who did not engage in sports prior to their IBD diagnosis increased their level of PA after their diagnosis [19].

A case control study discussed mild to moderate mobility limitations among adults with UC compared to age, gender, and body mass index matched healthy controls [35]. This discrepancy could be connected to evidence of the skeletal muscle changes associated with inflammation in adults with IBD [35]. Increased levels of pro-inflammatory markers increase the rate of muscle protein breakdown and reduce the rate of protein synthesis [35,42,43]. Chronic inflammation also compromises endothelial integrity, which reduces oxygen delivery to muscles [35,42,43]. In addition to muscular changes due to inflammation, IBD medications, such as corticosteroids and cyclosporine, can have a negative effect on skeletal muscles [42,44]. Based on this context of skeletal muscle dysfunction, adults with IBD should be encouraged to participate in exercise/PA to improve their muscle function, which can, in turn, result in long-term health benefits.

As evident in the literature, PA can help many chronic GI illnesses, including irritable bowel syndrome [45], diverticular diseases [46,47], and constipation [48], as well as reduce the risk of colon cancer [49]. In alignment with these studies, the reviewed research supported the benefits of PA for IBD which is a chronic illness with a disease trajectory of remission and relapse. The reviewed studies highlighted the positive effects of PA on QOL; the improvement of mental, physical, and IBD symptoms; the reduction of the risk of IBD; and the protective role of PA in maintaining remission. Overall, the reviewed studies favored low-to moderate-intensity physical activities for adults with IBD.

There are mixed opinions in published literature regarding the type and intensity of PA for adults with IBD, especially related to high-intensity exercises. In a mouse model of colitis, worsened inflammation and increased mortality were observed with forced treadmill exercise [50]. Conversely, reduced inflammatory responses in the distal colon and reduced diarrheal episodes were noted after 30 days of voluntary wheel training [50]. Intense exercise increased systemic inflammation and the level of cytokines, resulting in worsened GI symptoms [10].

However, in a qualitative analysis, participants had different views about PA [51]. Some participants were actively engaged in exercise, and they reported having more energy. Conversely, others reported a vicious circle between fatigue and exercise, where low energy prohibited them from engaging in exercise, which led to a more sedentary life [51]. Therefore, a dose-effect approach should be considered with PA/exercise in adults with IBD when considering the type of exercise, the intensity, and the duration [10]. Additionally, disease activity can be a confounding factor and patients with mild form of disease activity may engage in exercise more frequently resulting in improved IBD outcomes [11]. Although a number of reviewed studies [14,15,21,27,39] included participants with active IBD, all these studies failed to establish a positive link between PA and active disease. A number of factors can influence PA engagement during active disease including bowel urgency, toilette access and the commencement of corticosteroids and biologics [7,11,22,39]. Those with mild form of disease activity may engage in exercise more frequently resulting in improved IBD outcomes. Conversely, those with moderate or severe disease activity may have decreased frequency of PA due to pain or cramping. Further research is needed to determine PA and IBD outcomes by disease levels: mild, moderate, and severe.

None of the reviewed studies offered any specific guidelines for PA in adults with IBD. Participants of the majority of the reviewed studies engaged in walking and running as the aerobic form of PA. Although resistance training and combined aerobic exercise or resistance training were reported safe for adults with IBD, data are limited on these types of PA. Only a few studies [26,32,36] evaluated the effects of resistance training and combined aerobic exercise or resistance training in adults with IBD. However, limitations were noted in these studies including small sample sizes, and, study participants had mild disease activity or were in remission. Because participants reported that they determined the duration of exercise based on their energy levels and recommended the same strategy to others with IBD [29], we recommend individually tailored PA for adults with IBD to maximize participation and resulting PA benefits. The same notion along with the dose-effect approach [10] need to be considered while providing PA advice to adults with IBD. However, the study participants reported a lack of discussion about the health benefits of exercise from their providers [29]. The same concern was raised in another study where 46.1% of the participants (n = 158) confirmed a lack of discussion regarding exercise by their health care professionals [19].

Similar to the reviewed studies, published literature lack guidelines on PA specific for adults with IBD [22]. A recent publication [7] addressed this concern and made some recommendations based on FITT (frequency, intensity, time and type) criteria which are: taking part in moderate PA three to five times a week for at least 30 minutes (can increase the time depending on the tolerance); selecting an activity that intensifies the energy expenditure to moderate intensity is pivotal to manage inflammation; participating in both aerobic and resistance training; engaging in group PA to maximize group support and to sustain the behavior [7]. Lastly, the authors recommended future N-of -1-trials with PA due to the varying disease course of IBD with a focus on physical and psychological outcomes [7]. However, the authors solely made these recommendations based on their scoping review on PA in adults with IBD without evidence-based studies. Therefore, the applications of these recommendations are not tested. Future studies focusing the FIIT criteria and N-of -1-trials are needed to validate these recommendations in adults with IBD.

In general, the reviewed studies supported moderate-intensity PA for adults with IBD. The reviewed studies highlighted many positive health benefits of PA, such as improvements in QOL and IBD symptoms, mental health benefits, and reduced risk of development of IBD. The results of the studies also indicated many barriers to performing PA for adults with IBD. Therefore, a dose-effect approach is recommended for PA engagement among adults with IBD.

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

Supplementary Material

Supplementary materials are available at the Intestinal Research website (https://www.irjournal.org).

Table 1.

Summary of Physical Activity Characteristics

| Author (year) | PA characteristics |

|---|---|

| Artom et al. (2017) [14] | 64% participated in aerobic exercise > 30 min/wk. |

| Aluzaite et al. (2019) [15] | ↑ PA associated with lower fatigue and ↑ sitting worsened fatigue. |

| Cabalzar et al. (2019) [37] | Participants with CD engaged in similar PA (sitting, standing, and walking) compared to controls; adults with CD were lying down more often compared to controls. |

| Chae et al. (2016) [16] | Most of the participants engaged in mild form of exercise. 80% of participants were eager to receive more information on PA. 28% preferred to exercise at home, 22% at local fitness center, and 38% did not have a preference. |

| Chan et al. (2014) [17] | 32% were exercising daily; walking, running/jogging and gym exercises were the common types of exercises reported. |

| Cronin et al. (2019) [32] | Subjects in the exercise group participated in a combination of moderate intensity aerobic and resistance exercise program × 8 weeks under the supervision of a gym instructor. |

| Crumbock et al. (2008) [30] | The majority of the participants (52.9%) were engaged in high levels of PA. |

| DeFilippis et al. (2015) [18] | 186 Participants were regularly engaged in exercise, and 51% were involved in moderate intensity exercise. |

| Gatt et al. (2019) [19] | ↓ Exercise scores in both CD and UC after IBD diagnosis (P = 0.002). |

| Hlavaty et al. (2013) [20] | Infrequent PA (< 2 sporting activities per week) in childhood was associated with ↑ the risk of CD and UC. |

| Holik et al. (2019) [21] | Almost equal number of participants were engaged in low (n = 109; 30-minute walk), and moderate (n = 111; bicycle ride and gardening) PA daily; only 23 subjects participated in intensive PA (hard manual work, sports) daily. |

| Jones et al. (2015) [22] | 48% of participants with CD in remission and 57% of participants with active CD had PA scores < median (median GLTA score of 28 for participants with CD); 47% of participants in UC remission and 58% participants with active UC had PA scores < median (median GLTA score of 34 for participants with UC). |

| Khalili et al. (2013) [23] | Walking was the most common PA engaged by participants. |

| Klare et al. (2015) [33] | Supervised moderate intensity running 3 times/wk × 10 weeks. |

| Lykouras et al. (2017) [34] | Evaluated the cardiopulmonary measurements between active and inactive IBD. |

| Mack et al. (2010) [24] | Walking, gardening, swimming, and bicycling were the most commonly reported PAs. |

| McNelly et al. (2016) [40] | Patients were instructed to increase PA to > 30% based on a personalized goal and to document the details of their achievements in a diary. |

| Nathan et al. (2013) [29] | Participants were primarily engaged in low intensity exercise. |

| Participants engaged in walking, running, swimming, cycling, karate, and yoga. | |

| Ng et al. (2015) [25] | Case control study where exercise was explored as an environmental factor. Daily exercise lowered the risk of development of CD. |

| Ng et al. (2007) [31] | Exercise was provided as an intervention; the intervention group completed low intensity walking (unsupervised) × 30 minutes’ × 3 times/wk for 3 months. |

| de Souza Tajiri et al. (2014) [26] | Offered progressive quadriceps resistance training 2 times/wk × 8 weeks. |

| Taylor et al. (2018) [27] | Participants engaged in MVPA (> 150 min/wk,) and ↑ walking (> 60 min/wk). |

| Tew et al. (2016) [28] | Walking was the most common PA reported. |

| Tew et al. (2019) [36] | Supervised HIIT and MICT were provided to participants using the leg cycle for 12 weeks. |

| van Langenberg and Gibson (2014) [41] | Participants were checked about initiation of regular exercise in a follow-up assessment. |

| van Langenberg et al. (2015) [38] | Each participant (CD) wore an accelerometer around the waist for 24 hr/day (including sleep but excluding bathing, swimming, and showering) for 7 consecutive days to measure PA. |

| Wiestler et al. (2019) [39] | Each participant wore a biaxial accelerometer around the upper arm for 24 hr/day (including sleep but excluding swimming and showering) for 7 consecutive days to measure PA. |

| Zaltman et al. (2013) [35] | Body composition, muscle strength, and lower extremity functional performance was assessed. |

PA, physical activity; CD, Crohn’s disease; UC, ulcerative colitis; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; GLTA, Godin leisure time activity index; MVPA, moderate to vigorous physical activity; HIIT, high-intensity interval training; MICT, moderate-intensity continuous training; ↑, increased; ↓, decreased.

Table 2.

Summary of Study Results on QOL

| Author (year) | Study type | QOL |

|---|---|---|

| Ng et al. (2007) [31] | Pilot RCT | ↑ QOL (P < 0.05) |

| Wiestler et al. (2019) [39] | Cross-sectional study | +Correlation between PA & QOL (P = 0.03) |

| de Souza Tajiri et al. (2014) [26] | Pilot study | ↑ QOL (P < 0.0001) |

| Tew et al. (2019) [36] | Pilot RCT | ↑ QOL mean scores in the MICT group; statistical significance was not assessed. |

| Crumbock et al. (2008) [30] | Pilot cross-sectional study | + Correlation between PA and QOL (P = 0.02) |

| Taylor et al. (2018) [27] | Cross-sectional study | ↑ QOL with ↑ moderate to vigorous PA (> 150 min/wk, P < 0.001) and ↑ walking (> 60 min/wk, P < 0.01) |

| Klare et al. (2015) [33] | RCT | ↑ QOL social sub-scores (P = 0.023) |

Table 3.

Summary of Study Results on Fatigue

| Author (year) | Study type | Fatigue |

|---|---|---|

| van Langenberg and Gibson (2014) [41] | Longitudinal assessment | ↓ Physical fatigue in those who started an exercise program (P = 0.04). |

| McNelly et al. (2016) [40] | Pilot RCT | ↓ Fatigue scores in those who received exercise advice (P = 0.03). |

| Tew et al. (2019) [36] | Pilot RCT | ↓ In fatigue scores in the HIIT, MICT and control groups; statistical significance was not assessed. |

| Artom et al. (2017) [14] | Cross-sectional study | ↑ Levels of fatigue in those who engaged in < 30 minutes of aerobic exercise per week (P = 0.01). |

| Aluzaite et al. (2019) [15] | Cross-sectional study | Physical (P = 0.04) and mental (P = 0.006) fatigue lowered with ↑ PA. |

Table 4.

Summary of Study Results on Risk of IBD Development

| Author (year) | Study type | Risk of IBD development |

|---|---|---|

| Khalili et al. (2013) [23] | Prospective cohort study | ↑ PA lowered the risk of CD (for the trend, P = 0.007). |

| Ng et al. (2015) [25] | Case control study | Daily exercise ↓ the risk of development of CD (P = 0.02). |

| Hlavaty et al. (2013) [20] | Case control study | Infrequent PA (< 2 sporting activities per week) in childhood ↑ risk of CD (P < 0.001) and UC (P = 0.02). |

| Jones et al. (2015) [22] | Prospective study | ↑ Exercise ↓ risk of active CD in adults with CD in remission (P = 0.02). |

| Gatt et al. (2019) [19] | Cross-sectional study | 41.3% of participants reported that exercise ↓ in relapse rates. |

REFERENCES

1. Bamias G, Pizarro TT, Cominelli F. Pathway-based approaches to the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Transl Res 2016;167:104-115.

2. Ng SC, Shi HY, Hamidi N, et al. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: a systematic review of population-based studies. Lancet 2018;390:2769-2778.

3. Stein DJ, Shaker R. Inflammatory bowel disease: a point of care clinical guide. London: Springer International, 2015.

4. Kappelman MD, Long MD, Martin C, et al. Evaluation of the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system in a large cohort of patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;12:1315-1323.

5. Knowles SR, Graff LA, Wilding H, Hewitt C, Keefer L, Mikocka-Walus A. Quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Part I. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2018;24:742-751.

6. Tabibian A, Tabibian JH, Beckman LJ, Raffals LL, Papadakis KA, Kane SV. Predictors of health-related quality of life and adherence in Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis: implications for clinical management. Dig Dis Sci 2015;60:1366-1374.

7. Eckert KG, Abbasi-Neureither I, Köppel M, Huber G. Structured physical activity interventions as a complementary therapy for patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a scoping review and practical implications. BMC Gastroenterol 2019;19:115.

8. Caspersen CJ, Powell KE, Christenson GM. Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public Health Rep 1985;100:126-131.

9. Saxena A, Fletcher E, Larsen B, Baliga MS, Durstine JL, Fayad R. Effect of exercise on chemically-induced colitis in adiponectin deficient mice. J Inflamm (Lond) 2012;9:30.

10. Bilski J, Mazur-Bialy AI, Brzozowski B, et al. Moderate exercise training attenuates the severity of experimental rodent colitis: the importance of crosstalk between adipose tissue and skeletal muscles. Mediators Inflamm 2015;2015:605071.

11. Engels M, Cross RK, Long MD. Exercise in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases: current perspectives. Clin Exp Gastroenterol 2017;11:1-11.

12. Pedersen BK, Saltin B. Exercise as medicine: evidence for prescribing exercise as therapy in 26 different chronic diseases. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2015;25 Suppl 3:1-72.

13. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097.

14. Artom M, Czuber-Dochan W, Sturt J, Murrells T, Norton C. The contribution of clinical and psychosocial factors to fatigue in 182 patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a cross-sectional study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2017;45:403-416.

15. Aluzaite K, Al-Mandhari R, Osborne H, et al. Detailed multi-dimensional assessment of fatigue in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Intest Dis 2019;3:192-201.

16. Chae J, Yang HI, Kim B, Park SJ, Jeon JY. Inflammatory bowel disease patients’ participation, attitude and preferences toward exercise. Int J Sports Med 2016;37:665-670.

17. Chan D, Robbins H, Rogers S, Clark S, Poullis A. Inflammatory bowel disease and exercise: results of a Crohn’s and Colitis UK survey. Frontline Gastroenterol 2014;5:44-48.

18. DeFilippis EM, Tabani S, Warren RU, Christos PJ, Bosworth BP, Scherl EJ. Exercise and self-reported limitations in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci 2016;61:215-220.

19. Gatt K, Schembri J, Katsanos KH, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease [IBD] and physical activity: a study on the impact of diagnosis on the level of exercise amongst patients with IBD. J Crohns Colitis 2019;13:686-692.

20. Hlavaty T, Toth J, Koller T, et al. Smoking, breastfeeding, physical inactivity, contact with animals, and size of the family influence the risk of inflammatory bowel disease: a Slovak case-control study. United European Gastroenterol J 2013;1:109-119.

21. Holik D, Včev A, Milostić-Srb A, et al. The effect of daily physical activity on the activity of inflammatory bowel diseases in therapy-free patients. Acta Clin Croat 2019;58:202-212.

22. Jones PD, Kappelman MD, Martin CF, Chen W, Sandler RS, Long MD. Exercise decreases risk of future active disease in patients with inflammatory bowel disease in remission. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2015;21:1063-1071.

23. Khalili H, Ananthakrishnan AN, Konijeti GG, et al. Physical activity and risk of inflammatory bowel disease: prospective study from the Nurses’ Health Study cohorts. BMJ 2013;347:f6633.

24. Mack DE, Wilson PM, Gilmore JC, Gunnell KE. Leisure-time physical activity in Canadians living with Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis: population-based estimates. Gastroenterol Nurs 2011;34:288-294.

25. Ng SC, Tang W, Leong RW, et al. Environmental risk factors in inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based case-control study in Asia-Pacific. Gut 2015;64:1063-1071.

26. de Souza Tajiri GJ, de Castro CL, Zaltman C. Progressive resistance training improves muscle strength in women with inflammatory bowel disease and quadriceps weakness. J Crohns Colitis 2014;8:1749-1750.

27. Taylor K, Scruggs PW, Balemba OB, Wiest MM, Vella CA. Associations between physical activity, resilience, and quality of life in people with inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J Appl Physiol 2018;118:829-836.

28. Tew GA, Jones K, Mikocka-Walus A. Physical activity habits, limitations, and predictors in people with inflammatory bowel disease: a large cross-sectional online survey. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2016;22:2933-2942.

29. Nathan I, Norton C, Czuber-Dochan W, Forbes A. Exercise in individuals with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Nurs 2013;36:437-442.

30. Crumbock SC, Loeb SJ, Fick DM. Physical activity, stress, disease activity, and quality of life in adults with Crohn disease. Gastroenterol Nurs 2009;32:188-195.

31. Ng V, Millard W, Lebrun C, Howard J. Low-intensity exercise improves quality of life in patients with Crohn’s disease. Clin J Sport Med 2007;17:384-388.

32. Cronin O, Barton W, Moran C, et al. Moderate-intensity aerobic and resistance exercise is safe and favorably influences body composition in patients with quiescent Inflammatory Bowel Disease: a randomized controlled cross-over trial. BMC Gastroenterol 2019;19:29.

33. Klare P, Nigg J, Nold J, et al. The impact of a ten-week physical exercise program on health-related quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Digestion 2015;91:239-247.

34. Lykouras D, Karkoulias K, Triantos C. Physical exercise in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis 2017;11:1024.

35. Zaltman C, Braulio VB, Outeiral R, Nunes T, de Castro CL. Lower extremity mobility limitation and impaired muscle function in women with ulcerative colitis. J Crohns Colitis 2014;8:529-535.

36. Tew GA, Leighton D, Carpenter R, et al. High-intensity interval training and moderate-intensity continuous training in adults with Crohn’s disease: a pilot randomised controlled trial. BMC Gastroenterol 2019;19:19.

37. Cabalzar AL, Azevedo FM, Lucca FA, Reboredo MM, Malaguti C, Chebli JMF. Physical activity in daily life, exercise capacity and quality of life in patients with Crohn’s disease on infliximab-induced remission: a preliminary study. Arq Gastroenterol 2019;56:351-356.

38. van Langenberg DR, Papandony MC, Gibson PR. Sleep and physical activity measured by accelerometry in Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015;41:991-1004.

39. Wiestler M, Kockelmann F, Kück M, et al. Quality of life is associated with wearable-based physical activity in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a prospective, observational study. Clin Transl Gastroenterol 2019;10:e00094.

40. McNelly AS, Nathan I, Monti M, et al. The effect of increasing physical activity and/or omega-3 supplementation on fatigue in inflammatory bowel. Gastroenterol Nurs 2016;14:39-50.

41. van Langenberg DR, Gibson PR. Factors associated with physical and cognitive fatigue in patients with Crohn’s disease: a cross-sectional and longitudinal study. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2014;20:115-125.

42. Reboredo MM, Pinheiro BV, Chebli JMF. Physical exercise programmes in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis 2017;11:1286.

43. Shephard RJ. The case for increased physical activity in chronic inflammatory bowel disease: a brief review. Int J Sports Med 2016;37:505-515.

44. Otto JM, O’Doherty AF, Hennis PJ, et al. Preoperative exercise capacity in adult inflammatory bowel disease sufferers, determined by cardiopulmonary exercise testing. Int J Colorectal Dis 2012;27:1485-1491.

45. Johannesson E, Simrén M, Strid H, Bajor A, Sadik R. Physical activity improves symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol 2011;106:915-922.

46. Stollman N, Smalley W, Hirano I, AGA Institute Clinical Guidelines Committee. American Gastroenterological Association Institute Guideline on the management of acute diverticulitis. Gastroenterology 2015;149:1944-1949.

47. Williams PT. Incident diverticular disease is inversely related to vigorous physical activity. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2009;41:1042-1047.

48. Iovino P, Chiarioni G, Bilancio G, et al. New onset of constipation during long-term physical inactivity: a proof-of-concept study on the immobility-induced bowel changes. PLoS One 2013;8:e72608.

49. Sellar CM, Courneya KS. Physical activity and gastrointestinal cancer survivorship. Recent Results Cancer Res 2011;186:237-253.

- TOOLS