Colitis and Crohn’s Foundation (India) consensus statements on use of 5-aminosalicylic acid in inflammatory bowel disease

Article information

Abstract

Despite several recent advances in therapy in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) therapy has retained its place especially in ulcerative colitis. This consensus on 5-ASA is obtained through a modified Delphi process, and includes guiding statements and recommendations based on literature evidence (randomized trials, and observational studies), clinical practice, and expert opinion on use of 5-ASA in IBD by Indian gastroenterologists. The aim is to aid practitioners in selecting appropriate treatment strategies and facilitate optimal use of 5-ASA in patients with IBD.

INTRODUCTION

Since the beginning of 21st century, incidence of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) has seen a steady rise in the emerging economies of Asia, Middle East, and South America [1]. Amongst the Southeast Asian countries, disease burden seems to be highest in India, with 2010 estimates pointing to an estimated IBD population of around 1.4 million [2]. There has been a progressively higher proportion of younger individuals being newly afflicted with the disease, along with ongoing aging of prevalent cases. Optimization of treatment modalities is critical as suboptimal disease management can lead to considerable morbidity and impairment of patients’ functional capacity [3].

5-Aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA; mesalamine/mesalazine) remains the drug of choice for management of a majority of patients with IBD. The anti-inflammatory effect of 5-ASA is through inhibition of lipoxygenase and cyclooxygenase enzymes, which in turn inhibit leucocyte chemotaxis to inflamed sites. 5-ASA can also activate peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ, and has antioxidant and free-radical scavenging properties [4-6].

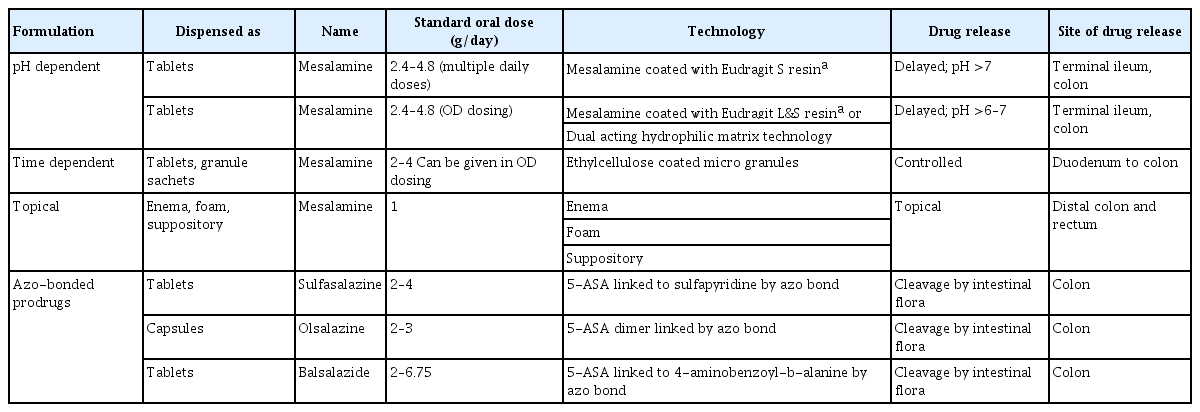

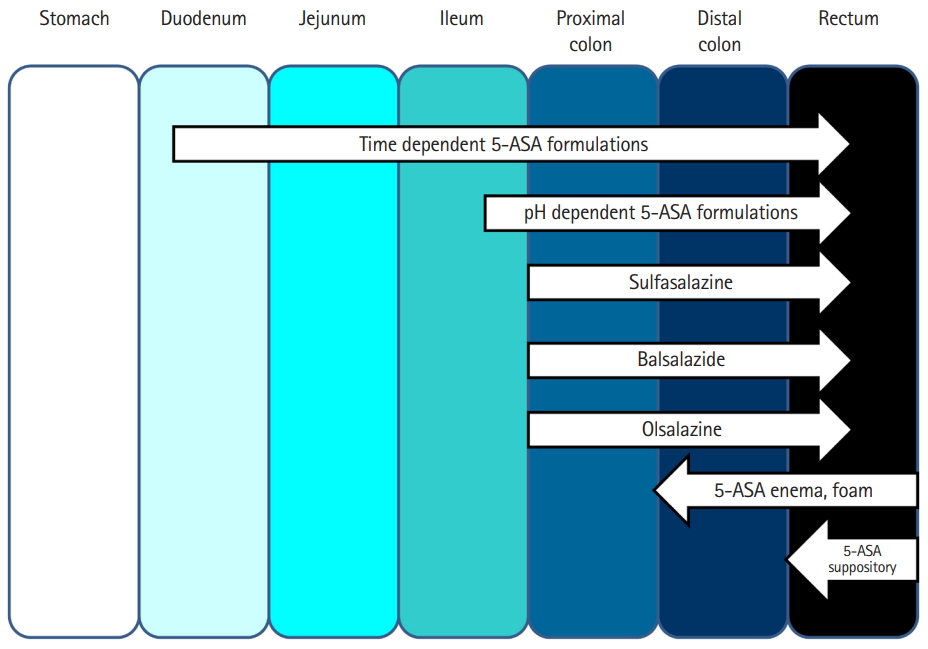

As the disease prevalence is on a steady rise, IBD management has come under the spotlight. Persistent efforts into research and development in IBD therapy have yielded several newer therapeutic options in recent years. However, 5-ASA has remained the drug of choice to date for management of a vast majority of patients with IBD. The journey of this seminal molecule in IBD started with the discovery of sulfasalazine. Over time it emerged that 5-ASA is the active therapeutic moiety [4,7,8]. The efficacy of 5-ASA formulation depends on its topical effect rather than on systemic absorption and redistribution to target sites (Fig. 1) [9-11]. 5-ASA blood concentration is not related to the dose taken [12]. This led to the development of newer 5-ASA drug delivery methods, aimed at minimizing systemic absorption and making maximum drug available at the inflamed epithelium [8]. These newer 5-ASA formulations (Table 1) [4,8,10,13-16] are not only efficacious but are also safe in the induction and maintenance of remission in IBD. They do not have the adverse effects of sulfasalazine, work locally at inflamed mucosa, and allow more proximal and pH-guided release (Fig. 1) [4,8].

Sites of 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) release from different formulations in the small and large intestine.

Despite their benefits in ulcerative colitis (UC), the new 5-ASA formulations exhibit limited utility in Crohn’s disease (CD) [4,7-9]. The more recent formulations, such as microsphere encapsulated formulations, show a pH-independent delivery, with their site of release beginning at the duodenum and continuing throughout the intestinal tract [10], allowing their use in both UC and small-bowel CD [8]. Further improvements, like granular drug formulations, have resulted in better outcomes than tablet forms. Rectal formulations such as suppositories and enemas have allowed better access to distal disease, thereby improving outcome.

With 5-ASA being the most commonly used drug in IBD, a need was felt to develop guidelines that would help optimize 5-ASA usage.

METHODOLOGY

1. Sources and Search

A comprehensive literature search was carried out on MEDLINE, MedIndia, EMBASE, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials for relevant literature published on use of 5-ASA in IBD. All the guidelines, original articles, systematic reviews, meta-analyses and review articles were included. Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms used to coin search strategies were “5-ASA,” “5 aminosalicylic acid,” “ulcerative colitis,” “Crohn’s colitis,” “colitis gravis,” “inflammatory bowel disease,” “IBD,” “bowel diseases, inflammatory,” “idiopathic proctocolitis,” “mesalamine,” “sulfasalazine,” “olsalazine,” “balsalazide,” “mesalazine,” “Crohn disease,” “Crohn’s disease,” and “Crohn’s Enteritis.”

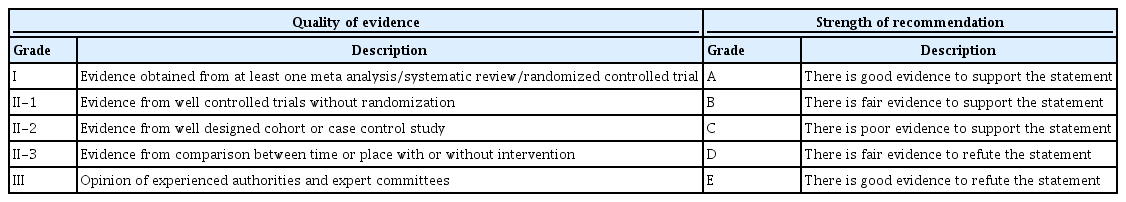

2. Review and Grading of Evidence

The Grading of Recommendation Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach was used to assess the quality of evidence in systematic reviews, randomized controlled trials (RCTs), observational studies and practice guidelines [17,18]. GRADE process helps in rating the quality of collected and summarized evidences based on explicit criteria that consider study design, risk of bias, and magnitude of effect. It also helps in considering whether the evidence is imprecise, inconsistent, or indirect. Recommendations were then classified as strong or weak based on the quality of the supporting evidence and after balancing the desirable and undesirable consequences of other management options [18]. The methodology used was a modified version of the scheme suggested by the Canadian Task Force on Periodic Health Examination [19]. The level of evidence was divided into I, II-1, II-2, II-3 and III; and grade of recommendations classified as A, B, C, D, and E (Table 2) [19,20].

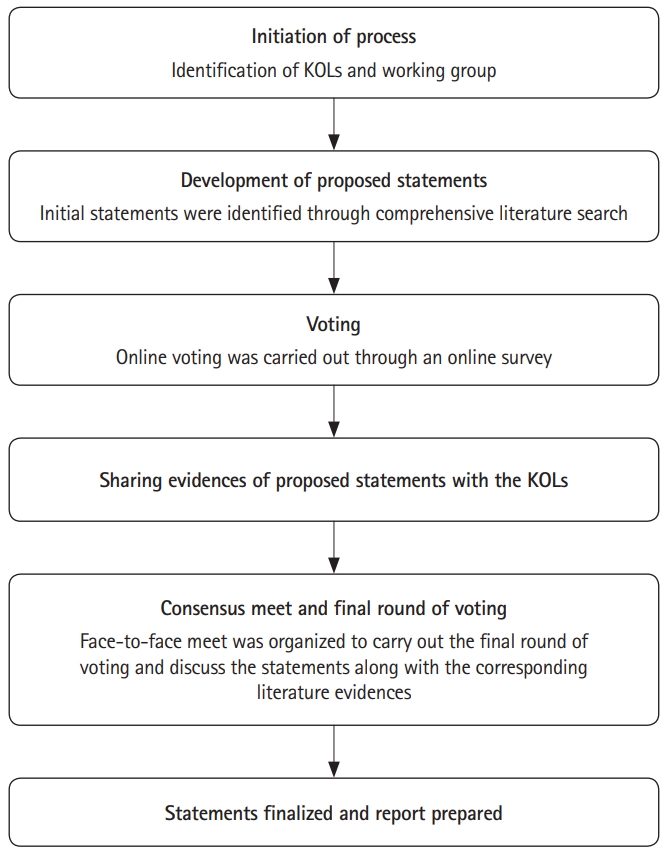

3. Consensus Process

A modified Delphi process was used for arriving at the consensus [21]. Based on literature search results, statements were proposed and were circulated amongst eminent gastroenterologists who are key opinion leaders (KOLs) in their field and region. Prior to sharing the proposed statements for voting, consent was sought from each prospective participant. Nine areas pertaining to the use of 5-ASAs in IBD were identified viz induction of remission, maintenance of remission, role of rectal 5-ASAs in UC, duration of use, role in CD, use in mother and child, side effects and monitoring, chemoprevention, and adherence. The questionnaire had one section for each of the areas. Each statement had 4 voting options: strongly agree, agree, disagree, and strongly disagree.

First round of voting was held through an anonymous online survey. After the first round of voting, the available evidence for the proposed statement in questionnaire was shared with the KOLs. A face-to-face meeting was held, where literature evidence was presented by 6 KOLs for each proposed statement. Based on discussion amongst the KOLs, a final round of voting (live anonymous vote using voting pads) was carried out during the meeting and consensus was achieved for each statement. When there was no consensus on a particular statement, it was modified. A second vote was sought for this modified statement and it was retained as a recommendation if voting was in favor and deleted if voting was against or inconclusive. The formal method that was used for development of consensus, based on the modified Delphi process is shown in Fig. 2 [21].

RECOMMENDATION STATEMENTS REGARDING 5-AMINOSALICYLATES

The recommended statements include the level of supporting evidence, grade of recommendation, and voting results. This is followed by a discussion of the supporting evidence. A summary of the recommended statements is provided in Table 3.

1. Role of 5-ASA in Induction of Remission in UC

Statement 1

5-ASA containing formulations are effective for induction of remission in patients with mild to moderate UC of any extent and are the first line of treatment for this indication.

• Grade of recommendation: A, Level of evidence: I, Voting: 87.5% strongly agree, 12.5% agree

Two RCTs conducted in 1960s have shown that sulfasalazine (2–4 g/day) was more effective than placebo in induction of remission. However, it was not well tolerated due to adverse events and high rates of discontinuation were observed [22,23]. Subsequently, all other 5-ASA formulations (low, standard, and high-dose mesalamine and diazo-bonded 5-ASAs) have been shown to be superior to placebo in inducing remission in adults with left-sided or extensive mild-to-moderate UC in a systematic review and network meta-analysis including 48 induction RCTs (n = 8,020) [24].

A Cochrane review conducted by Feagan and MacDonald (48 studies including RCTs; 7,776 patients) was further updated by Wang et al. (53 studies including RCTs, n = 8,548) to assess the efficacy of 5-ASA [25,26]. Wang et al. [26] found 5-ASA to be significantly superior to placebo for all outcome variables (failure to enter clinical remission 71% in 5-ASA vs. 83% in placebo group: relative risk [RR], 0.86; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.82–0.89) in active mild-to-moderate UC. The different formulations of 5-ASA (tablets, granules, pellets, delayed release preparations of mesalamine, balsalazide and olsalazine) did not differ in efficacy (failure to enter remission in patients on 5-ASA vs. patients on comparator 5-ASA 50% vs. 52%: RR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.86–1.02) [25,26].

For patients with mild to moderately severe UC, 5-ASA is widely accepted for use as first line therapy in induction of remission [10]. Head to head comparisons between 5-ASA and corticosteroids are very few [27]. A multicenter, randomized, single blind, parallel group study comparing beclomethasone and 5-ASA found similar efficacy in both treatment arms at 4 weeks (remission achieved in 63.0% vs. 62.5% of patients, respectively) [28].

Statement 2

In mild to moderate UC, 5-ASA (2–4.8 g/day) or sulfasalazine (3 g/day) should be given for induction of remission.

• Grade of recommendation: A, Level of evidence: I, Voting: 78.3% strongly agree, 21.7% agree

The Assessing the Safety and Clinical Efficacy of a New Dose of 5-ASA (ASCEND) trials were a series of dose-finding trials for 5-ASA in UC. A pooled analysis of 3 ASCEND trials showed no significant difference between 4.8 g/day and 2.4 g/day in mild to moderately active UC (RR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.78–1.01) [25,26]. Subgroup analysis however, showed that the patients with moderate UC benefited from a higher dose viz. 4.8 g/day [29].

In another systematic review and network meta-analysis by Nguyen et al. [24] when UC was stratified by disease severity (6 RCTs, n = 1,589 patients with extensive or left-sided mild to moderate UC), high-dose 5-ASA (> 3 g/day) was shown to be superior to standard-dose (2–3 g/day) for inducing clinical remission (RR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.86–0.99). Therefore, 5-ASA can be used in low dose (2.4 g/day) in mild UC and higher doses (4.8 g/day) can be used in moderately severe disease.

Sulfasalazine at a dose of 3 g/day has been used for inducing remission in patients with mild to moderate UC [4,16,30]. Two Cochrane systematic reviews showed that efficacy of different 5-ASA formulations and sulfasalazine was not significantly different (RR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.77–1.04) [25,26]. On the contrary, compared to diazo-bonded 5-ASAs, sulfasalazine was inferior in inducing clinical remission [24]. Furthermore, 5-ASA is better tolerated than sulfasalazine with 29% and 15% of patients experiencing adverse events on sulfasalazine and 5-ASA, respectively (RR, 0.48; 95% CI, 0.37–0.63) [25].

Statement 3

In distal or extensive mild to moderate UC, combination of topical and oral 5-ASA formulations is preferred over oral 5-ASA alone.

• Grade of recommendation: A, Level of evidence: I, Voting: 91.7% strongly agree, 4.2% agree, 4.2% disagree

A systematic review and meta-analysis of 4 RCTs found combined topical and oral 5-ASAs to be superior to oral 5-ASA alone in inducing remission in mild to moderate active leftsided UC, proctosigmoiditis, and proctitis (RR of no remission, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.47–0.91) [31]. Another systematic review and network meta-analysis (n = 8,020 patients with extensive or leftsided mild to moderate UC) reported that combined oral and rectal 5-ASA agents were superior to standard dose oral 5-ASA (2–3 g/day) for induction of remission (failure to induce remission with combined oral and rectal 5-ASAs; odds ratio [OR], 0.41; 95% CI, 0.22–0.77) [24]. Active comparisons of efficacy and tolerability showed that combined oral and rectal 5-ASAs were significantly superior to all other interventions for inducing remission in mild to moderate UC, except budesonide multi-matrix [24]. In the surface under the cumulative ranking curve analysis (SUCRA), combined oral and rectal 5-ASAs ranked highest in inducing remission (SUCRA, 0.99) followed by high-dose 5-ASA (SUCRA, 0.82) [24]. Considering 13% median remission rate for placebo across trials, approximately 63%, 33%, and 26% of patients treated with combined oral and rectal 5-ASA, high-dose and standard-dose 5-ASA, respectively, are expected to achieve clinical remission [24].

Statement 4

Once daily dose of oral sustained release preparation should be considered as it is equally effective as divided doses.

• Grade of recommendation: A, Level of evidence: I, Voting: 72.0% strongly agree, 28.0% agree

New, once daily (OD) formulations of 5-ASA use multi-matrix technology which involves incorporating 5-ASA into a lipophilic matrix, which itself is dispersed within a hydrophilic matrix, to delay and prolong the dissolution [32]. Two Cochrane systematic reviews have demonstrated no significant difference between OD versus conventional dosing for induction of remission (P = 0.49 and P = 0.34 respectively) [25,26]. In a metaanalysis (7 RCTs, n = 1,469), no significant differences were observed between OD and multiple dosing groups for induction of remission in mild to moderate UC (RR, 1.03; 95% CI, 0.97–1.10; P = 0.26) [33]. A single daily dose of 5-ASA should therefore be preferred as in addition to being equally efficacious, it improves patient compliance [34,35]. It should be taken into consideration that 5-ASA formulations available in India do not use multi-matrix technology. They use a dual matrix technology with L and S Eudragit coating.

Statement 5

A period of 2 weeks of 5-ASA therapy should be given before considering a patient as a nonresponder.

• Grade of recommendation: B, Level of evidence: I, Voting: 80.0% strongly agree, 20.0% agree

While selecting 5-ASA for induction of remission in patients with UC, the timing at which clinical response is evident also needs to be considered. Nonresponders to the recommended 5-ASA induction doses should be identified early, and therapy escalation should be considered in such cases.

Based on ASCEND (4.8 g/day, 800 mg tablet) I and II trials, symptoms of rectal bleeding and stool frequency either improved or resolved by day 14 in the majority of patients on both 4.8 g/day and 2.4 g/day of 5-ASA (73% vs. 61%, respectively). By day 14, symptom resolution was seen in 43% versus 30% of patients on 4.8 g/day versus 2.4 g/day dose (P = 0.035). Moreover, relief in symptoms after 2 weeks correlated with high rate of relief in symptoms after 6 weeks [36]. Hence, patients should be assessed at day 14 for therapeutic decision making.

Statement 6

Dose escalation to a maximum dose of 4–4.8 g may be done for patients who do not respond to lower initiating doses of 5-ASA compounds.

• Grade of recommendation: B, Level of evidence: I, Voting: 76.0% strongly agree, 24.0% agree

In the ASCEND I trial, subgroup analysis of patients with moderately active disease revealed that higher dose of 5-ASA was better by an absolute difference of 15% in achieving therapeutic success (72% vs. 57%, P = 0.038) [37]. ASCEND II confirmed a statistically superior effect of the 4.8g/day over the 2.4 g/day dose in moderately active disease (72% overall response vs. 59%, respectively) [38] and ASCEND III showed a significant benefit of 4.8 g/day versus 2.4 g/day in patients with difficult to treat UC, specifically those who required corticosteroids or more than 2 medications (corticosteroids, oral 5-ASA, rectal 5-ASA, or immunomodulators) for disease control in the past [39].

A systematic review and network meta-analysis (n = 8,020) has also ranked high-dose 5-ASA (> 3 g/day) superior to standard-dose 5-ASA (2–3 g/day) for induction of remission (failure to induce remission with high-dose 5-ASA; OR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.66–0.93) [25]. These trials suggest that in patients not responding to lower initiating doses of 5-ASA, dose escalation to 4.8 g/day should be tried by week 3 before considering addition of corticosteroids, immunosuppressants/immunomodulators or biologics for such cases.

Statement 7

Sulfasalazine may be preferred in patients with concomitant arthralgia/arthritis.

• Grade of recommendation: C, Level of evidence: III, Voting: 100.0% strongly agree

Articular involvement is the most common extraintestinal manifestation in IBD, with a prevalence ranging between 17% and 39% [40]. It frequently involves the axial joints but can also be associated with peripheral arthritis. Peripheral arthritis has 3 subtypes: type 1, pauciarticular, joint activity parallels intestinal disease activity, type 2, polyarticular form, affecting small joints with symptoms running independent from IBD course, and type 3, which includes both axial and peripheral forms [41-43].

The approach to management of arthritis in patients with IBD is similar to that in treatment of spondyloarthritis. While the treatment of axial arthritis focuses on combination of exercise and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NASIDs), selective conventional non-biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) are used for peripheral arthritis resistant to initial NSAID therapy, if biologics are not already required for axial or gastrointestinal disease manifestations [44].

Sulfasalazine is one such DMARD, which is an azo-bonded combination of 5-ASA and sulfapyridine. It is often poorly tolerated due to adverse effects (due to the sulfapyridine moiety) such as headache, nausea, vomiting, drug rash, hepatitis, and hematologic toxicity. This limits its use in IBD, for which safer 5-ASA compounds have been developed. However, an Italian Expert panel has recommended 2–3 g/day of sulfasalazine in mild to moderate IBD with peripheral arthritis and early disease that failed on intra-articular corticosteroids [45]. On the other hand, the Assessment in SpondyloArthritis international Society and European League Against Rheumatism do not recommend sulfasalazine for management of ankylosing spondylitis (and thus axial arthritis) [46]. Thus, sulfasalazine can be used in patients with IBD who have concomitant peripheral arthritis but may not be beneficial for those with axial arthritis.

Statement 8

In acute severe colitis, 5-ASA has no proven role as an adjunct therapy. 5-ASA should be introduced after clinical improvement.

• Grade of recommendation: C, Level of evidence: III, Voting: 59.3% strongly agree, 33.3% agree, 7.4% disagree

Acute severe UC is a medical emergency with high mortality. Intravenous corticosteroids remain the cornerstone of treatment, as they act rapidly and are effective in up to 70% of the patients [47,48]. 5-ASAs can be temporarily withdrawn while the patients are being treated with intravenous corticosteroids, as there is no evidence supporting benefit of these drugs in acute severe UC. Conversely, a paradoxical increase in diarrhea has been reported in 3% patients on 5-ASAs [48,49]. However, topical 5-ASA or corticosteroids may be added in patients who have high stool frequency [20]. After an initial response to the intravenous corticosteroids, patients can be switched to oral corticosteroids, and 5-ASA, azathioprine, or 6-mercaptopurine can be added [50].

2. Role of 5-ASA in Maintenance of Remission in UC

Statement 9

Long-term 5-ASA is indicated for maintenance of remission in patients with UC.

• Grade of recommendation: A, Level of evidence: I, Voting: 100.0% strongly agree

Statement 10

In patients with mild to moderate UC, the dose that was used for induction of remission should be continued for initial maintenance of remission.

• Grade of recommendation: B, Level of evidence: I, Voting: 53.8% strongly agree, 23.1% agree, 23.1% disagree

The safety and efficacy of long-term use of 5-ASA as a maintenance therapy has been studied in several studies and its continued use is known to prevent disease relapse in patients with UC [9,10].

A Cochrane review of 38 studies (n = 8,127) assessed efficacy, dose-responsiveness, and safety of oral 5-ASA for maintenance of clinical or endoscopic remission in UC. Forty-one per cent of 5-ASA patients relapsed compared to 58% of placebo patients (7 studies, 1,298 patients; RR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.62–0.77) [25,51]. Another network meta-analysis (28 RCTs; n = 4,218) also showed that all of the following were effective at remission maintenance; low dose 5-ASA (< 2 g/day), standard dose 5-ASA (< 2–3 g/day), high-dose 5-ASA (> 3 g/day). Diazo bonded 5-ASAs and combined oral and rectal 5-ASAs were significantly superior to placebo in maintaining clinical remission in UC (diazo-bonded 5-ASAs: RR, 0.47; 95% CI, 0.35–0.62; oral and rectal 5-ASAs: RR, 0.21; 95% CI, 0.11–0.40). Sulfasalazine tended to be superior to placebo in maintaining clinical remission in UC (RR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.57–1.17) [24].

A randomized open-label study including 156 UC patients in remission, who had experienced a disease relapse within previous 3 months, were randomized to receive either 2.4 g/day or 1.2 g/day 5-ASA dose for 12 months. The patients on 2.4 g/day dose had significantly higher mean number of days to relapse than those prescribed 1.2 g/day dose (mean ± standard deviation: 175 ± 126 vs. 129 ± 95.3, P < 0.001, respectively) [52]. In patients who experienced ≤ 3 relapses/year in the 3 years prior to enrollment, more number of the patients in the 2.4 g/day group were maintained in remission than in the 1.2 g/day group [52].

Statement 11

5-ASA maintenance dose reduction can be considered in patients with UC having mild clinical course with complete mucosal healing.

• Grade of recommendation: B, Level of evidence: II-1, Voting: 73.1% strongly agree, 19.2% agree, 7.7% disagree

Mucosal healing in UC is associated with improved clinical outcomes in terms of lower relapse rates [53-55], lesser requirement for immunosuppressive agents [56], fewer hospitalizations and colectomies [56,57], lower risk of colorectal cancer [58-60] and improved quality of life [61,62]. Achieving complete mucosal healing should, therefore, be the primary endpoint of treatment.

Besides mucosal healing, various factors including adherence to treatment, duration of disease in remission, degree of mucosal healing (complete/partial), and clinical course should be considered before reducing the maintenance dose of 5-ASA.

No difference in the long-term risk of flare was noted between low (2.4–2.8 g/day) versus high (4.4–4.8 g/day) dose 5-ASA in patients who adhere to treatment [63]. Data from an IBD registry showed that a longer duration (> 2 years) of disease remission correlated with a lower risk of relapse (P < 0.001) [64]. In another randomized, double-blind withdrawal study using 5-ASA 1.2g/day, patients were allocated to 2 groups according to length of previous remission. In the group in remission for over 24 months, withdrawal of 5-ASA did not influence the relapse rates [65].

No difference was found in another study in relapse rates at 1 year on 5-ASA 1.2 g compared with 2.4 g/day. However, for patients with extensive UC, 5-ASA agents in a dose of 1.2 g/day were inferior to 2.4 g/day for long-term maintenance of remission (P < 0.005). The 1.2 g/day dose was also significantly (P = 0.01) inferior to 2.4 g/day for patients with frequently relapsing disease [52].

A recent study, including UC patients in remission, showed that 5-ASA dose reduction is more successful in sustaining remission if Mayo endoscopic sub-score of 0 is achieved [66]. In the MOMENTUM trial, of patients who achieved remission during induction with high-dose multi-matrix 5-ASA, 47.8% of patients in complete remission and 26% of patients in partial remission could achieve/maintain remission after 12 months at a reduced dose of 2.4 g/day (OR, 2.61; 95% CI, 1.76–3.87; P < 0.001) emphasizing that patients achieving complete remission before dose reduction were more likely to sustain remission [67].

Complete withdrawal of 5-ASA agents is currently not recommended unless the patient is intolerant as there is some evidence that regular 5-ASA reduces the risk of colorectal cancer [68]. Hence, the decision of dose reduction should be undertaken with caution and may be considered in patients with mild disease course and where mucosal healing has been observed for at least 2 years.

Statement 12

For patients with moderate to severe UC who required corticosteroids for induction of remission, 5-ASAs can be used for maintenance.

• Grade of recommendation: B, Level of evidence: II-2, Voting: 96.4% strongly agree, 3.6% agree

Use of corticosteroids for inducing remission is associated with an increased risk of subsequent clinical relapses [69]. Studies evaluating outcomes after systemic corticosteroid use have shown that up to 30%–40% patients subsequently require medical rescue therapies or colectomy [70-72].

In a cohort of UC patients treated with 5-ASA after a course of oral systemic corticosteroids, 75% patients relapsed (median, 29 months; range, 1–156 months), and 14% required colectomy (median, 11 months; range, 1–24 months). Kaplan Meier curve showed relapse and colectomy rates over 1 year of 26% and 11%, respectively [73]. Khan et al. [74] also reported that 65% of patients who achieved clinical remission with corticosteroids required retreatment with steroids within 2 years. Seventy-two percent relapse rate at 83 months follow-up in patients with steroid induced remission was reported in another study [75].

The use of corticosteroids as maintenance therapy is restricted by lack of long-term efficacy, and associated side-effects [76,77]. In a report from an IBD registry on patients receiving 5-ASA as maintenance therapy for UC, Fukuda et al. [64] concluded that patients with history of steroid use have a tendency to relapse. These patients can be maintained on 5-ASA therapies or on thiopurines. For those not willing for thiopurines, 5-ASA therapy is a suitable option. However, the dose of 5-ASA should not be reduced, especially in patients with previous corticosteroid use, as these patients are at risk for clinical relapse.

Statement 13

Patients with proctitis can be maintained with 3 g weekly divided dose of topical 5-ASA or low dose of oral 5-ASA (2–2.4 g daily).

• Grade of recommendation: A, Level of evidence: I, Voting: 55.6% strongly agree, 40.7% agree, 3.0% strongly disagree

Rectal 5-ASA is first-line maintenance therapy in ulcerative proctitis. An RCT with 95 ulcerative proctitis patients found 5-ASA suppositories at a dose of 1 g thrice a week to be more effective than placebo in maintaining remission [78]. Another RCT reported a significantly higher relapse rate at 12 and 24 months with placebo as compared to OD 500-mg 5-ASA suppository (P < 0.001) [79]. A systematic review and meta-analysis evaluating topical 5-ASA therapies for maintenance of remission in ulcerative proctitis also reported the benefit of rectal 5-ASA (pooled RR, 2.80; 95% CI, 1.21–6.45; degree of heterogeneity [I2], 66%; P = 0.02) [80]. Another recent meta-analysis including 7 RCTs (n = 555), showed that topical 5-ASA was effective in preventing relapse of distal UC [81]. The superiority of rectal 5-ASA over placebo for maintenance of remission at 1 year was also demonstrated in a recent Cochrane review (RR, 2.22; 95% CI, 1.26–3.90) [82].

Two RCTs have compared combination treatment with oral 5-ASA plus intermittent 5-ASA enema and oral 5-ASA alone, for maintenance of remission. One compared patients who received 1 g 5-ASA enemas twice a week plus oral 5-ASA 3 g/day for 7 days with daily oral 5-ASA only and the other compared combined therapy with 5-ASA tablets 1.6 g/day and 5-ASA enemas 4 g/100 mL twice weekly with oral 5-ASA tablets 1.6 g/day and placebo enemas/twice weekly [83,84]. Higher remission rates were reported in patients receiving combination therapy.

Long-term tolerance and adherence to rectal therapy is variable [85,86]. Oral 5-ASAs associated with better patient compliance could be an alternative if rectal therapies are not tolerated. The newer oral 5-ASA formulations including the ethylcellulose coated as well as multi-matrix 5-ASA have been shown to achieve therapeutic levels in the distal colon [87,88].

3. Role of Rectal 5-ASA Formulations in UC

Statement 14

In patients with proctitis, suppositories should be preferred over enemas or foams.

• Grade of recommendation: A, Level of evidence: I, Voting: 88.9% strongly agree, 11.1% agree

Statement 15

Recommended dosage of topical therapy with 5-ASA suppository for induction of remission is 1 g OD.

• Grade of recommendation: A, Level of evidence: I, Voting: 92.3% strongly agree, 7.7% agree

Statement 16

In ulcerative proctitis, topical 5-ASA formulations in the form of suppository/enema, is the first line of therapy. Patients not responding to topical treatment can be given a combination of oral and topical 5-ASA.

• Grade of recommendation: A, Level of evidence: I, Voting: 87.0% strongly agree, 13.0% agree

Various 5-ASA rectal formulations (enemas, foams, and suppositories) are available for treatment of ulcerative proctitis. Suppositories target the site of the inflammation in the rectum and the distribution mirrors the extent of disease. Foams and enemas can act topically in the sigmoid and descending colon respectively and therefore are preferred treatment in left-sided colitis [89,90].

Römkens et al. [91] in their meta-analysis (2,513 patients using rectal 5-ASA) reported mucosal healing rates of 62%, 51%, and 46% for suppositories (8 study arms), foams (9 study arms), and enema (23 study arms), respectively. On subgroup analysis, head to head comparison between 5-ASA foam and enema did not reveal significant difference between the preparations. Because suppositories are used in patients with proctitis and represent a different group of patients, direct comparison with other preparations were not done.

Additionally, during acute flares, enemas are generally less well tolerated as a larger volume of enema is difficult to retain because of active rectal inflammation [92-94]. OD topical therapy is as effective as divided doses. In a randomized clinical trial, 5-ASA 1 g OD suppository was compared with conventional 500 mg twice a day 5-ASA suppository in patients with active distal UC. The OD treatment resulted in quicker induction of clinical and endoscopic remission and was better tolerated than twice daily group (P < 0.01) [95]. Another randomized multicenter trial demonstrated non-inferiority of 1 g OD 5-ASA suppository versus 500 mg 5-ASA suppository thrice-daily, with patients preferring the OD regime [96]. There is no dose response for topical therapy above a dose of 1 g 5-ASA daily [97].

Although 5-ASA suppositories produce earlier and significantly better results than oral 5-ASA in the treatment of active ulcerative proctitis, patients intolerant/nonresponsive to rectal 5-ASA alone can be treated with oral 5-ASA in combination with rectal 5-ASA therapies [98,99].

A double-blind comparison of oral versus rectal 5-ASA versus combination therapy in the treatment of distal UC concluded that combination of oral and rectal 5-ASA was more effective than either alone [100]. Another randomized multicenter study demonstrated a significantly higher rate of improvement in UC-Disease Activity Index (UC-DAI) within 2 weeks with the combined oral 5-ASA/enema therapy (P = 0.032) in extensive colitis [101]. There are no trials of combination therapy for proctitis alone.

Statement 17

In patients with proctitis not responding to oral and rectal 5-ASA, topical corticosteroids can be added for inducing remission.

• Grade of recommendation: A, Level of evidence: I, Voting: 76.0% strongly agree, 24.0% agree

Two meta-analyses have shown that topical 5-ASA is more effective than topical corticosteroids, in inducing symptomatic, endoscopic, or histological remission [97,102]. However, in patients not responding/intolerant to 5-ASA (topical, oral or a combination of both) within 2–3 weeks of initiating therapy, combination therapy of topical 5-ASA and topical corticosteroids can be considered [94]. A randomized, double-blind trial demonstrated higher efficacy of beclomethasone dipropionate (BDP) and 5-ASA enema combination therapy (BDP/5-ASA) versus BDP or 5-ASA alone. The combination was significantly superior to single-agent therapy in terms of improved endoscopic and histological scores [103].

4. How Long to Use 5-ASAs?

Statement 18

Withdrawal of 5-ASAs is associated with a significant risk of relapse. Decision to withdraw should only be made after several factors are taken into consideration such as duration of remission and mucosal healing.

• Grade of recommendation: B, Level of evidence: I, Voting: 42.9% strongly agree, 46.4% agree, 10.7% disagree

Multiple factors determine the duration of treatment with 5-ASA. A recent Cochrane review suggested that 5-ASA was superior to placebo as a maintenance therapy in UC [82]. These findings endorse a lifelong approach to therapy with 5-ASA in UC. However, dose reduction after induction of remission has been evaluated in various studies.

In a real-world OPTIMUM study, no difference was found between reduced dose and maintained dose for maintenance of remission after induction. Also, maintenance of remission was noted to be significantly better than placebo in patients in whom duration of remission was > 12 months (hazard ratio [HR] for relapse, 0.600; 95% CI, 0.486–0.740; P < 0.0001 for > 12 months and HR, 0.352; 95% CI, 0.289–0.431; P < 0.0001 for > 24 months). 5-ASA therapy was not withdrawn in any of the patient [104]. In a retrospective Korean study, left-sided or extensive colitis at time of diagnosis (HR, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.01–2.10; P = 0.04) was observed to be independent predictor for clinical relapse on 5-ASA therapy [105].

Although 5-ASA preparations are generally well tolerated, adverse reactions including worsening colitis; nephrotoxicity, interstitial lung disease, bronchiolitis obliterans, pancreatitis, hair loss, and Stevens-Johnson syndrome have been described [106]. These can also be major determinants in deciding continuation or withdrawal of the therapy.

Mucosal healing (endoscopic/histological) also predicts the subsequent clinical course. Narang et al. [107] showed that histological remission predicts a sustained clinical remission (87.1% patients in histological remission remained asymptomatic at 1 year). Another RCT showed that 5-ASA dose reduction is more successful in sustaining remission if a Mayo endoscopic sub-score of 0 is achieved [66]. Attainment of mucosal healing might help decide upon the withdrawal or discontinuation of the drug.

Complete withdrawal of 5-ASA agents is currently not recommended unless the patient is intolerant as there is some evidence that regular 5-ASA reduces the risk of colorectal cancer [68].

Statement 19

In patients with proctitis with mucosal healing, oral 5-ASA may be discontinued with continuation of rectal suppositories.

• Grade of recommendation: C, Level of evidence: III, Voting: 92.6% strongly agree, 7.4% agree

A meta-analysis involving 3,977 patients on oral 5-ASA (granules and tablets) and 2,513 patients on rectal 5-ASA (suppositories, enema, and foam) demonstrated that mucosal healing rates are superior with rectal formulations (36.9% and 50.3% for patients treated with oral and topical mesalamine, respectively) [91]. Another systematic review by Ford et al. [81] that studied the relative efficacies of different routes of administration of 5-ASA agents also concluded that intermittent topical 5-ASAs are superior to oral 5-ASA in maintaining remission in quiescent UC.

Though there is no direct evidence showing the benefit of discontinuing oral 5-ASA and continuing suppositories in patients with proctitis who have achieved mucosal healing, the expert panel recommends that oral 5-ASA may be discontinued with continuation of rectal suppositories in such patients.

5. Role of 5-ASA in CD

Statement 20

Sulfasalazine may be considered for induction of remission in mild to moderate colonic CD.

• Grade of recommendation: B, Level of evidence: I, Voting: 37.5% strongly agree, 54.2% agree, 8.3% disagree

A Cochrane meta-analysis has evaluated the role of aminosalicylates in induction of remission or response in CD. A pooled analysis of 3 studies [108-110] showed that sulfasalazine was not superior to placebo for induction of remission or response at 17 to 26 weeks of follow-up (RR, 1.52; 95% CI, 0.95–2.43; P = 0.08); however, because of sparse data and heterogeneity the results had low quality of GRADE evidence [108]. A subsequent comparison of 2 RCTs [109,110]. after removing the source of heterogeneity revealed a favorable response with sulfasalazine over placebo after 17–18 weeks of follow-up (RR, 1.38; 95% CI, 1.00–1.89; P = 0.05; zero heterogeneity; and moderate quality of evidence). There was no difference in adverse events between sulfasalazine and placebo arms [108]. The benefit however was limited to patients with Crohn’s colitis. Those patients with small bowel disease or those who continued to have active disease even after previous corticosteroid and sulfasalazine exposures were not likely to benefit [108,109]. The 5-ASA formulations do not have efficacy in isolated colonic CD.

Statement 21

5-ASA formulations are not indicated for induction of remission in ileal/ileocolonic/proximal small intestinal CD.

• Grade of recommendation: A, Level of evidence: I, Voting: 63.0% strongly agree, 22.2% agree, 11.1% disagree, 3.7% strongly disagree

Comparison between sulfasalazine and corticosteroids showed that sulfasalazine monotherapy was inferior to corticosteroids at 17–18 weeks of follow-up (RR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.51–0.91; P = 0.009; moderate quality of evidence due to sparse data) [108]. Another pooled analysis showed that controlled release 5-ASA (1–2 g/day) was not superior to placebo at 16 weeks of follow-up (RR, 1.46; 95% CI, 0.89–2.40; P = 0.14). There was no difference in proportion of patients having adverse effects [108].

A pooled analysis of 3 studies comparing 5-ASA (4 g/day) with placebo showed a nonsignificant mean difference in Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (CDAI) reduction (–19.8 points; 95% CI, –46.2 to 6.7; P = 0.14); another comparison of delayed release 5-ASA (3–4.5 g/day) with tapering dose conventional corticosteroids showed no significant difference in efficacy after 8–12 weeks of follow-up (RR, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.79–1.36) [108].

Comparison of 5-ASA 4 g/day with budesonide 9 mg/day showed that 5-ASA was significantly less effective than budesonide at 16 weeks (RR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.40–0.78; P < 0.001) [108]. There was significant difference in proportion of patients experiencing adverse effects, however, more patients withdrew from 5-ASA arm due to adverse effects. Another trial corroborated these findings when olsalazine 2 g/day led to a higher withdrawal rate, mainly due to diarrhea, as compared with placebo (P = 0.015) [108].

Although the Cochrane analysis has limitations of sparse data, trial heterogeneity and high risk of bias, yet, it has been sufficiently demonstrated that sulfasalazine was modestly effective, with benefit confined to Crohn’s colitis; and there is no proven role of 5-ASA in induction of remission in ileal/ileocolonic/proximal small intestinal CD.

Statement 22

There is no role of 5-ASA or sulfasalazine in maintenance of remission in a majority of patients with CD.

• Grade of recommendation: A, Level of evidence: I, Voting: 50.0% strongly agree, 37.5% agree, 12.5% disagree

The efficacy of sulfasalazine or 5-ASA in maintaining remission in CD is not documented [110,111]. A systematic review of 12 RCTs found no significant difference in relapse at 12 and 24 months between the 5-ASA and placebo arms. The relapse at 12 months was 53% in 5-ASA patients (dose 1.6–4 g/day) versus 54% placebo patients (RR, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.91–1.07; 11 studies, 2,014 patients) [112]. Likewise, 54% (31/57) of 5-ASA patients (dose 2 g/day) relapsed at 24 months compared to 58% (36/62) of placebo patients (RR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.68–1.29; 119 patients) [112].

However, 5-ASA may prove to be of utility in certain patients with CD as reported by a retrospective analysis by Danish Crohn Colitis Database Study among 165 CD patients. A long term benefit was observed with 5-ASA in 36% of the patients [113]. Twenty-three percent of patients became 5-ASA dependent (responding to re-introduction of 5-ASA on relapsing within a year of 5-ASA cessation or to dose escalation on relapsing on stable/reduced 5-ASA dose). Women were more likely than men to develop response to 5-ASA (OR, 2.89; 95% CI, 1.08–7.75; P = 0.04). Patients with longer disease duration were more likely to show 5-ASA dependency (38% vs. 18%: OR, 4.06; 95% CI, 1.09–15.1; P = 0.04) [113].

Outcome on 5-ASA in CD is not associated with localization or behavior of disease, age, or history of surgery [113].

Statement 23

5-ASA has a role in postoperative prophylaxis following ileal resection in CD.

• Grade of recommendation: A, Level of evidence: I, Voting: 56.5% strongly agree, 39.1% agree, 4.3% disagree

A Cochrane systematic review of 23 RCTs that investigated medical therapies for postoperative CD recurrence reported that clinical recurrence and severe endoscopic recurrence reduced significantly with 5-ASA as compared with placebo (RR for clinical recurrence, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.62–0.94; number needed to treat [NNT] = 12; RR for severe endoscopic recurrence, 0.50; 95% CI, 0.29–0.84; NNT = 8). Risk of serious adverse events was lower with 5-ASA versus azathioprine/6-mercaptopurine (RR, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.30–0.89) but risk of any endoscopic recurrence was higher (RR, 1.45; 95% CI, 1.03–2.06). 5-ASA therapy did not differ significantly from azathioprine/6-mercaptopurine for any other outcome [49].

Another Cochrane systematic review of 9 RCTs found that 5-ASA was significantly more effective than placebo in postoperative prophylaxis of CD (OR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.52–0.90), but there was no difference in efficacy between 5-ASA and thiopurines (OR, 1.08; 95% CI, 0.63–1.85) [114].

6. Use of 5-ASA in Pregnant/Lactating Women and Children with IBD

Statement 24

5-ASA agents are the first line therapy for induction and maintenance of remission in children with UC.

• Grade of recommendation: A, Level of evidence: I, Voting: 70.8% strongly agree, 29.2% agree, 4.2% disagree

5-ASAs are recommended as first-line therapy for induction and maintenance of remission of mild to moderate UC in children [115,116]. 5-ASA therapy should be used for maintenance indefinitely unless intolerant, as it is highly effective and has a good safety profile.

A prospective cohort study successfully reported clinical remission at week 3 in 42% pediatric patients treated with the combination of 5-ASA oral and enema (1 g/day) [117]. In a randomized, double-blind, active control study, pediatric UC patients treated with high and low-dose 5-ASA for a period of 6 weeks demonstrated similar efficacy in improving Pediatric UC Activity Index (55% vs. 56% of the patients in high- and low-dose of 5-ASA, respectively) (P = 0.924) as well as Truncated Mayo score (70% vs. 73%) [118]. An RCT comparing efficacy of once and twice daily dosing of 5-ASA in inducing remission in children with UC did not find any significant difference in the rates of induction of remission (60% vs. 63%, P = 0.78) [119].

A meta-analysis including 37 RCTs revealed that 5-ASA is highly effective for induction of remission (RR of no remission 0.79 with 5-ASAs; 95% CI, 0.73–0.85; NNT = 6). Higher effect was observed at ≥ 2.0 g/day dose (RR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.85–0.98) [120]. However, there is no increase in remission rates at doses of > 2.5 g/day.

5-ASA is also effective in preventing relapse of quiescent UC as compared to placebo (RR of relapse, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.55–0.76; NNT = 4). Doses ≥ 2.0 g/day were more effective in preventing relapse as compared to < 2.0 g/day (RR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.64–0.97) [120]. A multicenter, double-blind study on 68 patients with mild-to-moderate active UC in the age range 5 to 17 years, reported an achievement of clinical improvement in 45% and 37% of patients who received 5-ASA agent (oral balsalazide) 6.75 and 2.25 g/day, respectively while clinical remission was seen in 12% and 9% of patients respectively. The study supported the tolerability and safety profile of 5-ASA and its role in clinical remission in pediatric UC patients [121]. In another multicenter, randomized, double-blind study, 39% pediatric mild to moderate UC patients clinically improved with olsalazine and were asymptomatic after 3 months, compared to 79% on sulfasalazine (P = 0.006); however, side effects were slightly less frequent with olsalazine [122]. Heyman et al. [123] suggested that a daily dose of 500 mg 5-ASA suppository to be safe and effective in pediatric ulcerative proctitis patients. At weeks 3 and 6, the mean Disease Activity Index values, with daily bedtime 500 mg 5-ASA suppository, decreased from 5.5 at baseline to 1.6 and 1.5, respectively (P < 0.001).

A meta-analysis including 20 RCTs comparing 5-ASA and sulfasalazine however, yielded nonsignificant differences. The RR for overall improvement was 1.04 (95% CI, 0.89–1.21; P = 0.63), RR for relapse was 0.98 (95% CI, 0.78–1.23; P = 0.85), RR for any adverse events was 0.76 (95% CI, 0.54–1.07; P = 0.11), and RR for withdrawals due to adverse events was 0.78 (95% CI, 0.46–1.3; P = 0.33) [124].

Statement 25

Suggested dosing is oral 5-ASA 60 to 80 mg/kg/day to 4.8 g daily; rectal 5-ASA 25 mg/kg up to 1 g daily; sulfasalazine 40–70 mg/kg/day up to 4 g daily.

• Grade of recommendation: B, Level of evidence: I, Voting: 72.7% strongly agree, 27.3% agree

An RCT enrolled 83 pediatric patients (age group: 5–17 years) who were treated with low dose delayed release 5-ASA viz. 27–71 mg/g/day and high dose delayed release 5-ASA viz. 53–118 mg/g/day. Both low- and high-dose arms demonstrated similar efficacy in 81 of 83 modified intent to treat population in short term treatment of mild to moderate active UC [118]. In another Phase I RCT, 52 children with UC, aged 5 to 17 years, and stratified by weight (18–82 kg), received multi-matrix 5-ASA at doses of 30, 60, or 100 mg/kg/day OD (maximum 4,800 mg/day) for 7 days. Children and adolescents with UC had pharmacokinetic profiles of 5-ASA and metabolite acetyl5-ASA similar to historical adult cohort [125]. Children can therefore receive a dose that is similar to the adult dose.

In an open-label trial 5-ASA 500 mg suppository daily at bedtime was found to be efficacious and safe in children with ulcerative proctitis [123]. 5-ASA enemas in the dose of 25 mg/kg (up to 1 g) daily for 3 weeks along with oral dose, can induce clinical remission and response in 42% and 71% pediatric UC patients, respectively, after 3 weeks [117].

Statement 26

Treatment with 5-ASA or sulfasalazine, if effective, should be continued during pregnancy as available evidence does not suggest adverse fetal outcomes.

• Grade of recommendation: A, Level of evidence: I, Voting: 77.3% strongly agree, 22.7% agree

Safety of 5-ASA therapy was established in a meta-analysis including 642 pregnant IBD patients treated with 5-ASA, sulfasalazine or olsalazine. There was no significant increase in the risks of stillbirth (OR, 2.38; P = 0.32), spontaneous abortion (OR, 1.14; P = 0.74), preterm delivery (OR, 1.35; P = 0.26) low birth weight (OR, 0.93; P = 0.96) and congenital abnormalities (OR, 1.16; P = 0.57) [126]. 5-ASA and sulfasalazine have been found to be safe in placebo-controlled studies in doses up to 3 g/day [127-129]. Folate supplementation has been recommended along with sulfasalazine. However, doses higher than 3 g/day might increase the risk of congenital malformations, premature birth, miscarriage, and fetal nephrotoxicity [127-129].

Presence of dibutylphthalate (DBP) in certain 5-ASA preparations, (using > 190 times the recommended human dose) is associated with an increased risk of development of skeletal malformations and reproductive adverse effects in animals. However, there are little data on effects of DBP among humans [130].

Statement 27

5-ASA is safe in lactating mothers.

• Grade of recommendation: C, Level of evidence: II-3, Voting: 68.0% strongly agree, 32.0% agree

Breast feeding might be protective against early onset IBD [131]. Sulfasalazine is of low risk during breastfeeding as confirmed by multiple prospective clinical trials [132]. Though sulfapyridine moiety is absorbed in minimal amounts and is excreted in breast milk, the milk/serum ratio is acceptable [131,133].

7. Side Effects and Monitoring of 5-ASAs

Statement 28

5-ASA is well tolerated by most patients.

• Grade of recommendation: A, Level of evidence: I, Voting: 100% strongly agree

A systematic review and meta-analysis showed that the likelihood of experiencing any adverse event with 5-ASAs was not statistically different when compared with placebo both for induction of remission (10 RCTs: RR, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.81–1.29) and in prevention of relapse (5 RCTs: RR, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.84–1.15) [120].

A Cochrane systematic review with 53 RCTs of parallel design, with minimum treatment duration of 4 weeks (n = 8,548) concluded that the difference in incidence of adverse events with 5-ASA agents and placebo did not reach statistical significance. However, sulfasalazine was not as well tolerated by the patients as 5-ASA (29% vs. 15% experiencing adverse events: RR, 0.48; 95% CI, 0.37–0.63) due to intolerance or hypersensitivity reactions that are often attributable to sulfapyridine moiety [26].

Statement 29

Paradoxical worsening of colitis may occur on initiation of 5-ASA due to drug hypersensitivity and requires discontinuation of the drug.

• Grade of recommendation: A, Level of evidence: I, Voting: 66.7% strongly agree, 33.3% agree

A systematic review of 46 randomized trials on short-term adverse effects of 5-ASA agents in UC reported that approximately 3% of patients on oral 5-ASA agents develop paradoxical worsening of their symptoms such as abdominal pain, diarrhea and blood in stools, and cramping [134]. Symptoms usually disappear when 5-ASA agents are discontinued. These patients should be considered allergic to 5-ASAs, drug should be withdrawn, and no 5-ASA preparation should be used in these patients [134].

The precise mechanism of exacerbation of colitis induced by 5-ASA is not clear. Scheurlen et al. [135] mentioned that diarrhea caused by 5-ASA was attributed to a secretory mechanism secondary to inhibition of ileal and colonic Na+ K+ ATPase. Another proposed mechanism is an alteration of arachidonic acid metabolism manifesting as secretory diarrhea and malabsorption.

Statement 30

5-ASA may cause renal toxicity and therefore monitoring of renal function should be carried out at least once in a year.

• Grade of recommendation: A, Level of evidence: I, Voting: 63.6% strongly agree, 31.8% agree, 4.5% disagree

Nephrotoxicity is a rare adverse effect of 5-ASA therapy. Muller et al. [136] reported the incidence of nephrotoxicity in patients with IBD taking 5-ASA to be about 1/4,000 patients/year. Another systematic review reported less than 0.5% incidence of nephrotoxicity in patients with IBD consuming 5-ASA [137]. 5-ASA-related nephrotoxicity includes interstitial nephritis, glomerulonephritis, and minimal-change nephropathy with nephrotic syndrome [138]. Renal impairment is reported to occur as early as within 29 days and as late as 5 years [136,139]; 50% of cases present within 1 year of treatment initiation [137]. No relationship between type/dose of 5-ASA therapy and development of renal disease has been reported.

The time of diagnosis of 5-ASA nephrotoxicity and subsequent discontinuation of drug determines the course of renal impairment [140]. A review showed that if 5-ASA-associated nephrotoxicity is diagnosed within 10 months of initiation of 5-ASA, then 5-ASA withdrawal alone reverses the nephrotoxicity in 85% of cases; but when the diagnosis was made after 18 months of initiation, partial recovery was observed in only one-third of patients [141].

The Medicines Healthcare Regulatory Authority recommended checking serum creatinine levels at baseline and 3 monthly for the first year, 6 monthly for the next 4 years, and then annually [142].

Statement 31

Dose modification is not required in chronic renal failure except that renal function should be monitored more closely.

• Grade of recommendation: C, Level of evidence: III, Voting: 52.0% strongly agree, 44.0% agree, 4.0% disagree

Patients with preexisting renal dysfunction may be more likely to suffer 5-ASA nephrotoxicity than those with normal renal function [143]. There is lack of RCT on the safety of 5-ASA agents in IBD patients suffering from chronic kidney disease [137]. IBD patients are more susceptible to renal damage during acute exacerbations, such as during an acute episode of diarrhea [137]. Therefore, IBD patients with chronic kidney disease need close monitoring [144], especially in acute exacerbations of disease, in case of 5-ASA induced nephrotoxicity, and in patients with comorbid conditions known to affect renal functions, such as diabetes and hypertension [137,145-147].

Statement 32

Although sulfasalazine has the potential to cause decreased fertility in men, 5-ASA formulations do not affect fertility in men or women.

• Grade of recommendation: B, Level of evidence: II-1, Voting: 47.6% strongly agree, 42.9% agree, 9.5% disagree

Various studies have shown the reversible adverse effect of sulfasalazine therapy on fertility in males with IBD. However, no such effects were observed on fertility of female patients. Infertility due to sulfasalazine in males is attributed to its sulfapyridine component rather than 5-ASA, the therapeutically active component. Sulfasalazine leads to changes in sperm morphology, decreased sperm motility and sperm count [127-129,131,133,148]. Birnie et al. [149] reported abnormal semen production and oligospermia in 86% and 72% patients respectively, treated with sulfasalazine. However, infertility in males is reversible and preventable by switching sulfasalazine to other 5-ASA formulations [6,150]. Absence of sulfapyridine moiety in the newer 5-ASAs possibly mitigates the adverse effect of sulfasalazine on male fertility [151].

Statement 33

Folate supplementation is required with use of sulfasalazine, other 5-ASA formulations do not require it.

• Grade of recommendation: B, Level of evidence: II-3, Voting: 62.5% strongly agree, 29.2% agree, 4.2% disagree, 8.3% strongly disagree

Sulfasalazine therapy is known to decrease folate synthesis by inhibiting dihydrofolate reductase and reducing folate absorption. These effects are not observed with other 5-ASA formulations [129,152,153]. Folic acid supplementation in sulfasalazine treated pregnant women, decreases the incidence of oral clefts, fetal neural tube defects and cardiovascular anomalies in newborns [129,152]. Pregnant women with IBD being treated with sulfasalazine should receive higher doses of folic acid (2 mg/day) than pregnant women without IBD [128,131,133,150].

8. Chemopreventive Role of 5-ASA

Statement 34

Long-term 5-ASA therapy in extensive/distal colitis is possibly associated with reduced risk of colon cancer in UC.

• Grade of recommendation: B, Level of evidence: II-1, Voting: 26.9% strongly agree, 57.7% agree, 15.4% disagree

A systematic review (6 case-control studies) showed that 5-ASA use in IBD patients may have chemopreventive effect. Four of the 6 studies exhibited significant risk reduction with 5-ASA (P < 0.05), while risk reduction in the other 2 studies did not reach significance [154]. Qiu et al. [155] in their systematic review and meta analysis (26 observational studies; 15,460 patients) also reported significant decrease in colorectal cancer (CRC) in UC patients (OR, 0.46; 95% CI, 0.34–0.61) but not in CD patients (OR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.42–1.03). 5-ASA use correlated significantly with CRC (OR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.39–0.74) but not with dysplasia (OR, 0.47; 95% CI, 0.20–1.10). The meta-analysis further showed significant protective effect of 5-ASA only in clinical studies (OR, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.39–0.65) and not in population-based studies (OR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.46–1.09).

Another systematic review and meta-analysis of 17 observational case-control, retrospective cohort, population- and hospital-based studies showed that the use of 5-ASA correlated with reduced risk of CRC in UC (OR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.48–0.84) [156]. The chemopreventive efficacy of 5-ASA increased with higher average daily dose (sulfasalazine ≥ 2 g/day and 5-ASA ≥ 1.2 g/day; pooled OR, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.35–0.75). Population-based studies in this systematic review and meta-analysis also did not show significant chemo-protective effect [156]. In another systematic review 5-ASA use was found to be protective for CRC (RR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.51–0.94) and the effect was dose-dependent; the effect with sulfasalazine was marginally nonsignificant (RR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.51–1.01) [157].

A population-based study from the University of Manitoba IBD Epidemiology Database did not endorse the chemo-protective effect of 5-ASA for CRC. HRs for CRC among 5-ASA users were 1.04 (≥ 1 year of use: 95% CI, 0.67–1.62; P = 0.87) and 2.01 (≥ 5 years of use: 95% CI, 1.04–3.9; P = 0.038). Males, but not females, using 5-ASA for ≥ 5 years had an increased risk of CRC [158].

9. Adherence to 5-ASA Therapy

Statement 35

Adherence to 5-ASA therapy improves outcome in patients with IBD. Hence, patient education is important.

• Grade of recommendation: B, Level of evidence: II-2, Voting: 56.5% strongly agree, 39.1% agree, 4.3% disagree

Adherence to medication plays a significant role in the management of IBD as patients need long-term therapy. Non-adherence lowers the effectiveness of treatment and also increases cost of therapy. Non-adherence to therapy is a major concern. A self-reported survey from India revealed that 81% of patients were non-adherent to treatment, defined as taking 80% or less of the dose advised. The reasons for non-adherence (not mutually exclusive) were forgetfulness (77%), felt better (14.2%), high frequency of doses (10.1%), no effect of medications (7.9%), and non-availability of medications (2.3%). Non-adherent patients were three times more likely to develop a relapse as compared to those with adherence (OR, 3.38; 95% CI, 1.29–8.88; P = 0.012) [159].

In contrast, another study from northern India (266 IBD patients) showed that more than 80% of patients were adherent to their medications, adherence being the least for topical therapy. Higher education, professional occupation, and upper socio-economic status were associated with lower adherence to medications [160]. Two cohort studies found that non-adherent patients are likely to experience greater risk of disease relapse compared to those who are adherent (HR, 5.5; 95% CI, 2.3–13; P < 0.001 and RR, 1.44; 95% CI, 1.08–1.94; P = 0.014, respectively) [161,162].

Although there is paucity of data on the impact of health education on adherence in IBD, physician-patient relationship is important in improving adherence rates.

CONCLUSIONS

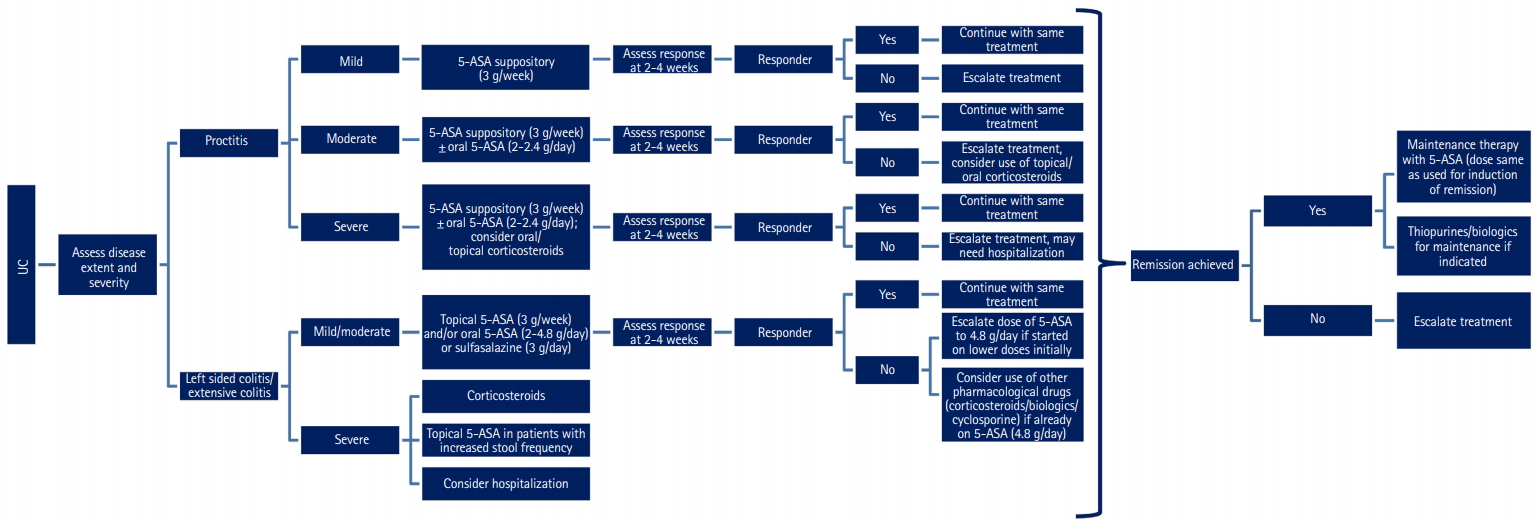

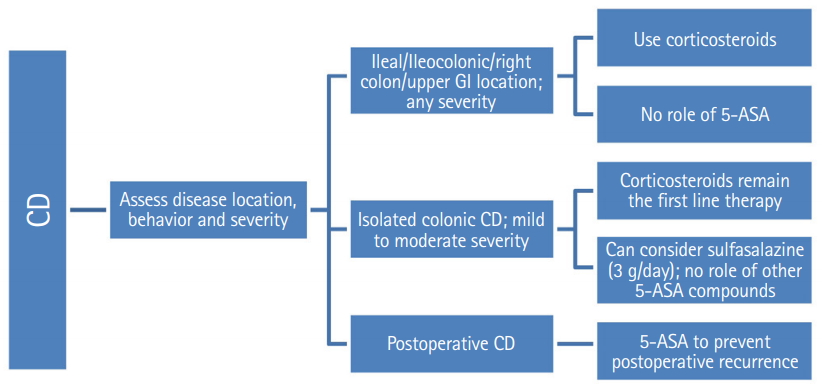

5-ASA is the most commonly prescribed drug for the treatment of IBD. It is effective, safe, and well-tolerated drug for treatment of mild to moderate UC. Evidence now suggests that there is a limited role for 5-ASA in CD. These consensus statements provide clarity on essential practical issues like indications for use of 5-ASA compounds, starting dose, dose escalation, efficacy and safety. These statements are likely to provide guidance to physicians on optimizing the use of 5-ASA for patients with IBD in clinical practice (Figs 3, 4).

Notes

FINANCIAL SUPPORT

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

Conception and design: Sood A, Ahuja A, Midha V. Supervision, analysis and interpretation of the data: Sood A, Ahuja A, Midha V. Collection of data: Sinha SK, Pai CG, Kedia S, Mehta V, Bopanna S, Abraham P, Banerjee R, Bhatia S, Chakravartty K, Dadhich S, Desai D, Dwivedi M, Goswami B, Kaur K, Khosla R, Kumar A, Mahajan R, Misra SP, Peddi K, Singh SP, Singh A. Drafting of the article: all authors. Critical revision of the article for important intellectual content: all authors. Final approval of the article: all authors.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the participation and inputs of Charles N Bernstein (University of Manitoba IBD Clinical and Research Centre, Max Rady College of Medicine, Rady Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada), Bo Shen (Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, USA) and Gursimran Kochar (Allegheny General Hospital, Pennsylvania, USA) in the formulation of this draft. The authors would also like to acknowledge Turacoz Healthcare Solutions (www.Turacoz.com), Gurugram, India, and Ferring (India), for their unrestricted educational support.