Risk factors for non-reaching of ileal pouch to the anus in laparoscopic restorative proctocolectomy with handsewn anastomosis for ulcerative colitis

Article information

Abstract

Background/Aims

Restorative proctocolectomy (RPC) with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis and handsewn anastomosis for ulcerative colitis requires pulling down of the ileal pouch into the pelvis, which can be technically challenging. We examined risk factors for the pouch not reaching the anus.

Methods

Clinical records of 62 consecutive patients who were scheduled to undergo RPC with handsewn anastomosis at the University of Tokyo Hospital during 1989–2019 were reviewed. Risk factors for non-reaching were analyzed in patients in whom hand sewing was abandoned for stapled anastomosis because of non-reaching. Risk factors for non-reaching in laparoscopic RPC were separately analyzed. Anatomical indicators obtained from presurgical computed tomography (CT) were also evaluated.

Results

Thirty-seven of 62 cases underwent laparoscopic procedures. In 6 cases (9.7%), handsewn anastomosis was changed to stapled anastomosis because of non-reaching. Male sex and a laparoscopic approach were independent risk factors of non-reaching. Distance between the terminal of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) ileal branch and the anus > 11 cm was a risk factor for non-reaching.

Conclusions

Laparoscopic RPC with handsewn anastomosis may limit extension and induction of the ileal pouch into the anus. Preoperative CT measurement from the terminal SMA to the anus may be useful for predicting non-reaching.

INTRODUCTION

Restorative proctocolectomy (RPC) with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis (IPAA) is a procedure used to treat patients with ulcerative colitis with refractory disease or when the patients develop neoplasms. This procedure was first described by Parks and Nicholls in 1978 [1]; the whole diseased colon and rectum are removed, while maintaining intestinal continuity without a permanent stoma. There are 2 techniques by which IPAA can be performed. As described by Parks and Nicholls, the procedure involves a mucosectomy with handsewn anastomosis, sometimes called ileal pouch-anal anastomosis (IAA). The second technique, which is called ileal pouch-anal canal anastomosis (IACA), uses a double-stapled anastomosis and was developed to improve postoperative function by preserving the anal transition zone and mucosa of the rectal stump; in this technique, a stapled anastomosis is made without mucosal resection [2]. Previous reports designated the history of colorectal neoplasia as a risk factor associated with developing other neoplasia in the residual rectum or anastomosis after radical colectomy [3]. Therefore, handsewn anastomosis with mucosectomy is considered desirable for cancer cases.

In handsewn anastomosis, the ileal pouch must be mobilized such that it may be extended by at least 2–4 cm into the pelvis, which may be challenging to achieve in all cases due to an inadequate length of the pouch pedicle. As a solution, a stapled anastomosis can be performed, which involves the omission of mucosectomy and improves the feasibility of anastomosis. A stapled anastomosis ensures that less tension is induced than with a handsewn anastomosis [4]. Therefore, in some cases, handsewn anastomosis with mucosectomy must be aborted and switched to stapled anastomosis or the scheduled procedure changed to abdominoperineal resection with a permanent ileostomy [5].

Several methods for enabling the ileal pouch to reach the anus have been reported, including sufficient mobilization of the small intestine, division of the mesenteric vessels supplying blood to the pouch, and performing transmesenteric incisions [6-16]. Cadaveric studies demonstrated the efficacy and safety of division of the ileocolic artery (ICA) or branches of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) [6,7,10,12,16], and surgical results of each technique in single-center studies have been reported [5,8,9,11,13,14,17].

Only few studies have investigated the risk of required abandonment of handsewn anastomosis because of the inability of the ileal pouch to reach the anus. Older age and severe obesity are established risk factors [5]. Ohira et al. [17] reported that the distance between the terminal branch of the ICA and the anal verge (AV), measured using axial computed tomography (CT), was a useful predictor of the difficulty to extend the ileal pouch to the anus.

More recently, the wider implementation of laparoscopic colorectal surgery has enabled laparoscopic IPAA for ulcerative colitis [18-21]. It remains unclear whether the laparoscopic approach itself is a risk factor for the pouch not reaching the anus, as well as what other risk factors are associated with the inability of the pouch to reach the anus in laparoscopic surgery. Therefore, in this study, we aimed to examine whether laparoscopic RPC with IPAA was a risk factor for the inability of the pouch to reach the anus and sought to identify other risk factors associated with this phenomenon.

METHODS

1. Surgical Procedures

In our hospital, we perform elective total proctocolectomy with mucosectomy and handsewn IPAA as the first-line surgery for patients who develop colitis-associated cancer or dysplasia. For refractory inflammation or acute exacerbation, most patients first undergo subtotal colectomy as an emergency operation, and remaining proctocolectomy with double-stapling anastomosis without mucosectomy as a secondary surgery 3–6 months later. However, some patients with severe inflammation around the lower rectum undergo handsewn anastomosis with mucosectomy. In this procedure, we make a 15-cm long ileal J-pouch, preserving the ICA [22]. The apex of the pouch is shifted 2 finger-breadths below the inferior border of the pubic symphysis. The mesentery of the small intestine is fully mobilized. If the pouch is unable to reach this far, 1–3 SMA branches to the ileal pouch are divided and the mesentery is fenestrated, while taking maximal care not to sacrifice blood perfusion of the intestine [8]. Patients with neoplasia or severe inflammation around lower rectum should not be treated with stapled IPAA in which rectal mucosa cannot be removed completely. Therefore, in these patients, our first alternative procedure in case the pouch does not reach the anus is open conversion in which we can keep pushing the J-pouch into the pelvis safely by hand until transanal anastomosis is completed. If the pouch does not reach even after open conversion, the surgical form should be changed to abdominoperineal resection with a permanent ileostomy is needed.

On the other hand, in patients without neoplasia or severe inflammation around lower rectum, we convert scheduled handsewn IPAA to stapled IPAA before trying handsewn anastomosis or open conversion.

2. Methods to Determine Risk Factors for Non-Reaching of the J-Pouch in Handsewn Anastomosis

The clinical records of 62 consecutive patients who were scheduled to undergo RPC with handsewn anastomosis for ulcerative colitis at the University of Tokyo Hospital between 1989 and 2019 were retrospectively reviewed.

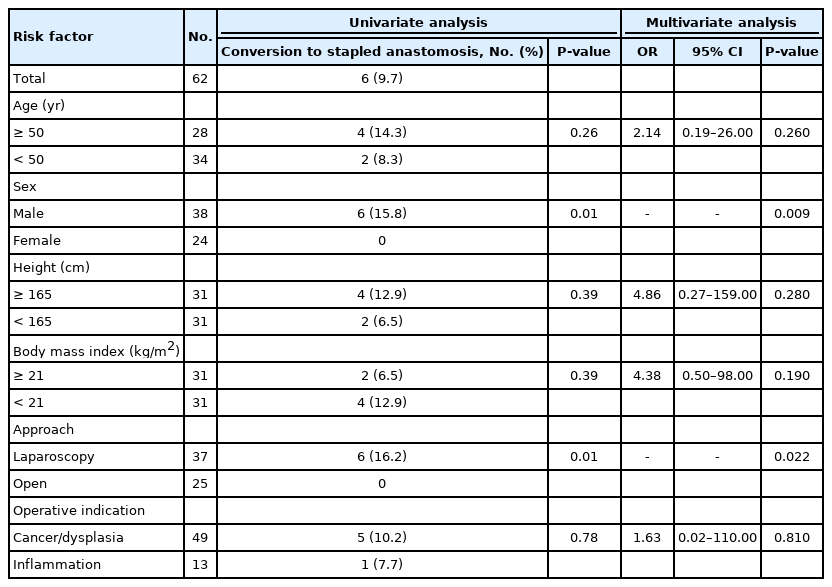

The risk factors for non-reaching were assessed by univariate and multivariate analyses for patients in whom the procedure had to be changed from handsewn anastomosis to stapled anastomosis because the pouch did not reach the anus. Age, sex, height, body mass index, surgical approach, and operative indications were evaluated. The risk factors for non-reaching of the ileal pouch to the anus in laparoscopic proctocolectomy with handsewn anastomosis were separately analyzed.

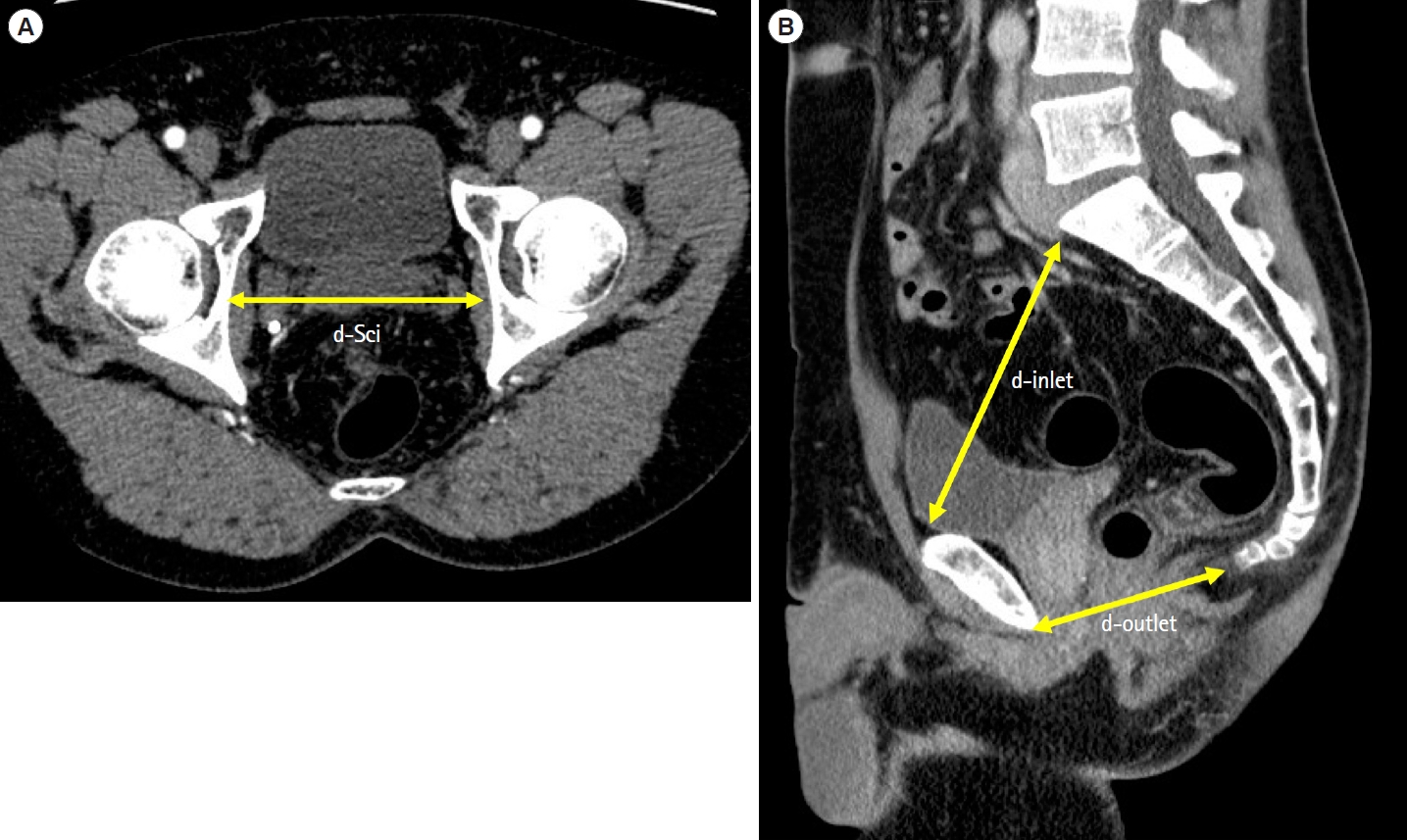

To investigate anatomical factors, we measured the distance between the horizontal contrast-enhanced CT slices that contain the root of the SMA (rSMA) and the terminal of the ileal branch of the SMA (tSMA; identifiable on the most caudal slice in the arterial phase of contrast-enhanced CT scans), and the upper margin of the anal canal (AC) (Fig. 1). The distance between the ischium at the level of the femoral head (d-Sci) in the axial view (Fig. 2A), from the promontory angle to the suprapubic margin (d-inlet), and from the coccyx to the inferior pubic margin (d-outlet) in the sagittal view, were also measured (Fig. 2B). CT studies taken after 2012 were performed using a multi-detector row (4–320 rows) helical CT scanner with a tube voltage of 120 kVp and a slice thickness of 5 mm. The contrast-enhanced images were reconstructed with a slice thickness of 1.25 mm. Three-dimensional reconstruction of SMA arterial branch was routinely performed. Before 2011, a slice thickness was 5 mm or 10 mm. Radiological assessment was performed by 2 board-certified colorectal surgeons (S.E. and K.M.; both of them were 16 years of experience).

The distances between the horizontal contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) slices that contain the root of the SMA (rSMA) and the terminal of the ileal branch of the SMA (tSMA), which can be identified on the most caudal slice in the arterial phase of contrast-enhanced CT scans, and the upper margin of the anal canal (AC) were measured. SMA, superior mesenteric artery.

The distances between the ischium at the level of the femoral head (d-Sci) in the axial view (A), from the promontory angle to the suprapubic margin (d-inlet), and from the coccyx to the inferior pubic margin (d-outlet), in the sagittal view (B), were also measured.

This study was approved by the local ethics committee of the University of Tokyo Hospital (approval No. 3252-(9)) and written informed consent for data use was obtained from all the patients enrolled in the study. This study was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

3. Statistical Analyses

Relationships between clinicopathological features and non-reaching of the J-pouch to the anus were evaluated using the chi-square test and Fisher exact test. Multivariate analyses were performed using logistic regression modelling. The t-test was used to compare continuous variables. P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using the JMP program, version 14.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Continuous values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

RESULTS

1. Patient Characteristics

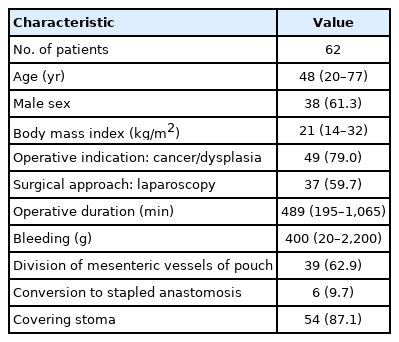

Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics of the patients. Thirty-seven of 62 patients underwent laparoscopic surgery, which included 4 hand-assisted laparoscopic surgeries and 1 robot-assisted laparoscopic surgery. Laparoscopic J-pouch surgery was first performed in 2003 in our department, and since 2012, all 31 patients have undergone laparoscopic surgery.

In 39 patients (62.9%), the SMA branch was dissected and the mesentery was fenestrated to allow extension of ileal pouch up to the anus. In 6 cases (9.7%), the scheduled handsewn anastomosis was changed to stapled anastomosis because we assessed the ileal pouch could not reach the anus, even after dissection of the SMA branch. In these 6 patients, even mucosectomy or open conversion was attempted because no neoplasia nor severe inflammation was existed in lower rectum. We decided to convert to stapled IPAA following our strategy described in the methods section. No patients underwent abdominoperineal resection or open conversion due to non-reaching.

2. Risk Factors for Non-Reaching of the J-Pouch in Handsewn Anastomosis

Risk factors for non-reaching of the J-pouch to the anus were analyzed (Table 2). In univariate analysis, male sex (P=0.01) and laparoscopic surgery (P=0.01) were risk factors of non-reaching. In multivariate analysis, male sex and laparoscopic surgery were independent risk factors of non-reaching.

In terms of surgical outcome, anastomotic leakage, anastomotic stenosis, small bowel obstruction, and pouchitis occurred in 1, 3, 15, and 9 patients, respectively. One of the 6 patients in whom handsewn anastomosis was abandoned due to non-reaching developed cancer in the residual rectal mucosa at 3 years after IPAA, and he underwent abdominoperineal resection as a salvage surgery.

3. Anatomical Features of Patients with Non-Reaching in Laparoscopic Handsewn Anastomosis

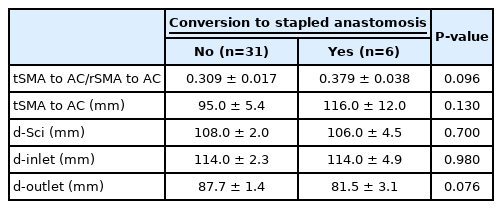

Anatomical features of the 37 patients who underwent laparoscopic surgery were also analyzed. The tSMA-to-AC and the rSMA-to-AC distances (mm) were 98.5 ± 30.4, 305.0 ± 19.3, and those of d-Sci, d-inlet, and d-outlet were 108.0 ± 11.0, 114.0 ± 11.8, and 86.6 ± 7.8, respectively. When these were analyzed as continuous variables, no significant differences between reaching and non-reaching patients were detected. However, in cases in whom the pouch did not reach, the tSMA-AC tended to be long and the d-outlet tended to be short (Table 3).

Comparison of Measured Values in Patients Who Were Scheduled to Undergo Laparoscopic RPC with Handsewn Anastomosis

Patients who underwent laparoscopic surgery were separately analyzed to assess the non-reaching risk (Table 4). None of the patients required conversion to open laparotomy. Division of the SMA branch and fenestration of the mesentery were performed in 28 patients (75.7%). Male sex remained a risk factor of non-reaching (P=0.02).

When the data were divided into 2 groups based on the median distances, the group having a distance ≥ 11 cm between the tSMA and the AC (P=0.045) had a greater risk of non-reaching. The small d-outlet group showed a tendency for non-reaching, but the difference did not reach statistical significance.

DISCUSSION

Our study findings suggest that laparoscopic RPC with handsewn anastomosis may limit the extension of the ileal pouch and its induction into the anus and that measuring the distance from the terminal SMA to the anus by preoperative CT may predict the tendency for non-reaching.

RPC with handsewn anastomosis with mucosectomy is a difficult procedure for general surgeons; thus, stapled anastomosis without mucosectomy has become widely implemented. However, it has been suggested that mucosectomy offers several important advantages, because leaving the diseased mucosa exposes the patient to the risk of carcinogenesis from the residual mucosa [4].

Various techniques for lengthening the mesentery have been studied, but there are cases in which RPC with handsewn anastomosis is technically difficult. Of the 1,789 IPAAs performed in the Mayo Clinic, IPAA could not be performed in 32 (1.8%) for technical reasons such as severe obesity, mesenteric obesity, and ischemia of the pouch region of the intestinal tract due to mesenteric distraction. A multivariate analysis reported that only age > 40 years was a risk factor in that cohort [5].

The frequency of high obesity and mesenteric obesity is reportedly lower in Japan than in Western countries. Nevertheless, there are a certain number of cases in whom handsewn anastomosis is not possible. Ikeuchi et al. [23] reported that RPC with handsewn anastomosis was possible in 923 (97.8%) of 944 RPCs, at a center with a high volume of RPC surgery. Although such centers may be familiar with the procedure, the possibility of the cases reflecting open surgery must be considered.

The laparoscopic IPAA procedure is more complicated than open surgery. The steps include mobilization and vascular division of the entire colon, dissection around the rectum to immediately above the anal canal, dissection of the terminal ileum, confirmation of ileal reaching, mesenteric lengthening, including vascular division and fenestration of the mesentery, additional mobilization, pouching preparation, mucosectomy from the anus, specimen removal, guiding the pouch to the anus, and performing a handsewn anastomosis. In these processes, it is often necessary to repeat the laparoscopic operation and create an alternative small laparotomy. In addition, it is difficult to reach the anus laparoscopically and to pull the pouch down sufficiently. Consequently, we considered it to be plausible that laparoscopic surgery was a risk factor for non-reaching. Consequently, in cases where mucosectomy is essential due to medical conditions (in cases where there is dysplasia of the rectum, cancer, or severe inflammation of the lower rectum), but where it is difficult for the pouch to reach the anus under laparoscopic conditions, conversion to laparotomy should be considered. In our series, handsewn anastomosis was possible in all the 6 cases of hand-assisted laparoscopic surgery in addition to all the 25 cases of open surgery, which may indicate keeping pushing the pouch into the pelvis by hand until transanal anastomosis is completed is very useful for making the pouch reach. We think we should not hesitate to convert to open surgery in cases the complete rectal mucosectomy is essential.

Given the difficulty of laparoscopic IPAAs, it is considered important to identify factors that predict non-reaching preoperatively. Ohira et al. [17] reported that mesenteric length, predictable from a CT scan, was a significant risk factor. They used terminal levels of ICA (tICA) that could be followed by CT and concluded that reaching of the pouch was problematic when the distance between the tICA and the AV exceeded 21 cm. We suspected that the tSMA was closer to the apex of the pouch and was a more sensitive indicator, and that the AC was more accurate than the AV. We showed that reaching of the pouch was difficult when the distance between the tSMA and AC exceeded 11 cm. Our results, similar to the Ohira et al. [17] study, showed that the pouch could more easily reach the anus in cases where the tSMA was more caudal. tICA to AV longer than 21 cm and tSMA to AC longer than 11 cm seems a considerable difference, but Ohira, et al. used the AV as a landmark while we used the upper edge of the anal canal. We thought tSMA might be more adaptable landmark compared to tICA because position of the apex of the J-pouch is more important than that of the ileocecum. On a CT scan, the small intestine falls into the small pelvis in some cases, but not in others. IPAA may be easier to perform in the former type of cases.

Furthermore, in our experience, performing surgery on cases with a narrow pelvis or with obesity is even more difficult. We investigated whether these anatomical factors could be risk factors. The indicator on pelvic size was based on a study by Akiyoshi et al. [24] who evaluated the relationship between pelvic size and difficulty of laparoscopic surgery for rectal cancer. No previous studies had attempted to analyze pelvic size as a factor in IPAA. Although no significant difference was found in this study, it was suggested that the d-outlet may be a useful index. The last step of retracting the pouch laparoscopically into the anus requires much skill, and the results are consistent with clinical experience. Strictly, we could not know if the pouch really would not reach the anus without trying. However, predicting “reachability” preoperatively may be quite useful.

The greatest advantage of this study is that none of the CT indices used required complicated calculations or three-dimensional reconstructions and could be easily obtained before surgery in any hospital. However, our study had several limitations. First, the findings were based on single-center data and the sample size was small. Because of the nature of this operation, it is difficult to collect a large sample size, and thus there is a need for studies that analyze multicenter data. Second, information of preoperative backwash ileitis was missing. Chronic inflammation could shorten the length of intestine. At least, there was no backwash ileitis in 6 cases who were needed to conversion to stapled anastomosis. Third, because no CT scans were available for older cases, no anatomical study was possible with open IAA. However, we could analyze anatomical features of all laparoscopic IAAs, which may pose a high risk of non-reaching. It is also important to seek further indicators in future. Fourth, tSMA could be modality and imaging condition dependent.

In conclusion, it may be more difficult to extend the pouch up to the anus in laparoscopic IPAA than in laparotomy. In particular, for men and individuals whose preoperative distance from the tSMA to the AC on preoperative CT images exceeds 11 cm, it is necessary to consider in advance that IPAA with handsewn anastomosis may need to be abandoned, and to prepare to change over to stapled anastomosis or open surgery if necessary.

Notes

Funding Source

This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C: grant number; 19K09137, 19K09115).

Conflict of Interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Author Contribution

Conceptualization: Emoto S. Data curation: Emoto S. Formal analysis: Emoto S. Funding acquisition: Emoto S, Tanaka T, Ishihara S. Investigation: Emoto S. Methodology: Emoto S, Nishikawa T, Shuno Y. Project administration: Emoto S. Resources: Emoto S, Iida Y, Ishii H, Yokoyama Y, Anzai H. Software: Emoto S. Supervision: Hata K. Validation: Emoto S. Visualization: Emoto S. Writing - original draft: Emoto S. Writing - review & editing: Nozawa H, Kawai K, Sasaki K, Kaneko M, Murono K, Sonoda H, Ishihara S. Approval of final manuscript: all authors.