1. Turner D, Ricciuto A, Lewis A, et al. STRIDE-II: an update on the Selecting Therapeutic Targets in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (STRIDE) Initiative of the International Organization for the Study of IBD (IOIBD): determining therapeutic goals for treat-to-target strategies in IBD. Gastroenterology 2021;160:1570-1583.

3. Ol├®n O, Erichsen R, Sachs MC, et al. Colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis: a Scandinavian population-based cohort study. Lancet 2020;395:123-131.

4. Tsai L, Ma C, Dulai PS, et al. Contemporary risk of surgery in patients with ulcerative colitis and CrohnŌĆÖs disease: a meta-analysis of population-based cohorts. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021;19:2031-2045.

5. Shah SC, Itzkowitz SH. Colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: mechanisms and management. Gastroenterology 2022;162:715-730.

6. Mir-Madjlessi SH, Farmer RG, Easley KA, Beck GJ. Colorectal and extracolonic malignancy in ulcerative colitis. Cancer 1986;58:1569-1574.

7. Lu C, Schardey J, Zhang T, et al. Survival outcomes and clinicopathological features in inflammatory bowel disease-associated colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg 2022;276:e319-e330.

9. Watanabe T, Konishi T, Kishimoto J, et al. Ulcerative colitis-associated colorectal cancer shows a poorer survival than sporadic colorectal cancer: a nationwide Japanese study. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2011;17:802-808.

10. Laine L, Kaltenbach T, Barkun A, et al. SCENIC international consensus statement on surveillance and management of dysplasia in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 2015;148:639-651.

11. Murthy SK, Feuerstein JD, Nguyen GC, Velayos FS. AGA clinical practice update on endoscopic surveillance and management of colorectal dysplasia in inflammatory bowel diseases: expert review. Gastroenterology 2021;161:1043-1051.

13. Ueno H, Mochizuki H, Hashiguchi Y, et al. Risk factors for an adverse outcome in early invasive colorectal carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2004;127:385-394.

14. Wang AY, Hwang JH, Bhatt A, Draganov PV. AGA clinical practice update on surveillance after pathologically curative endoscopic submucosal dissection of early gastrointestinal neoplasia in the United States: commentary. Gastroenterology 2021;161:2030-2040.

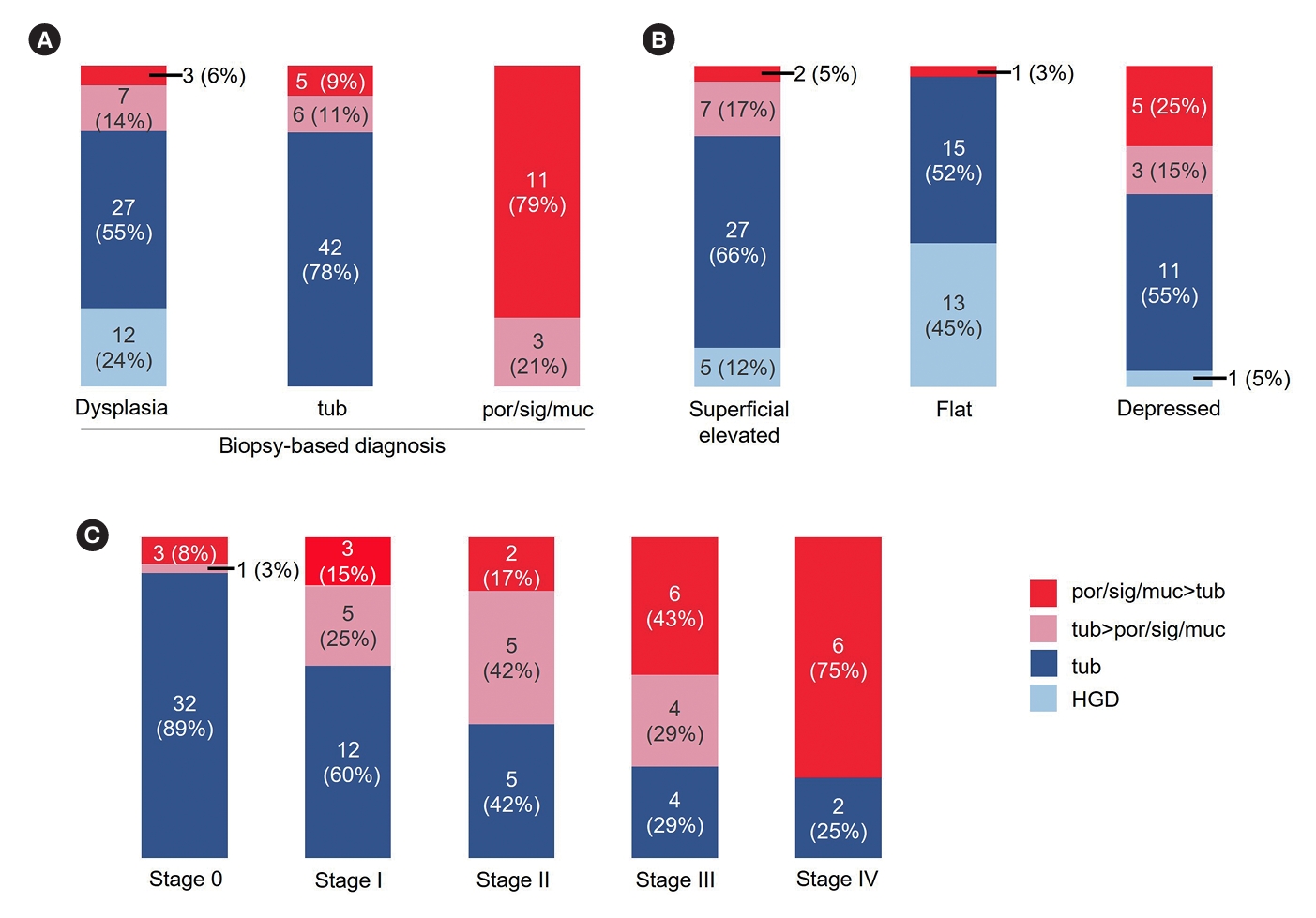

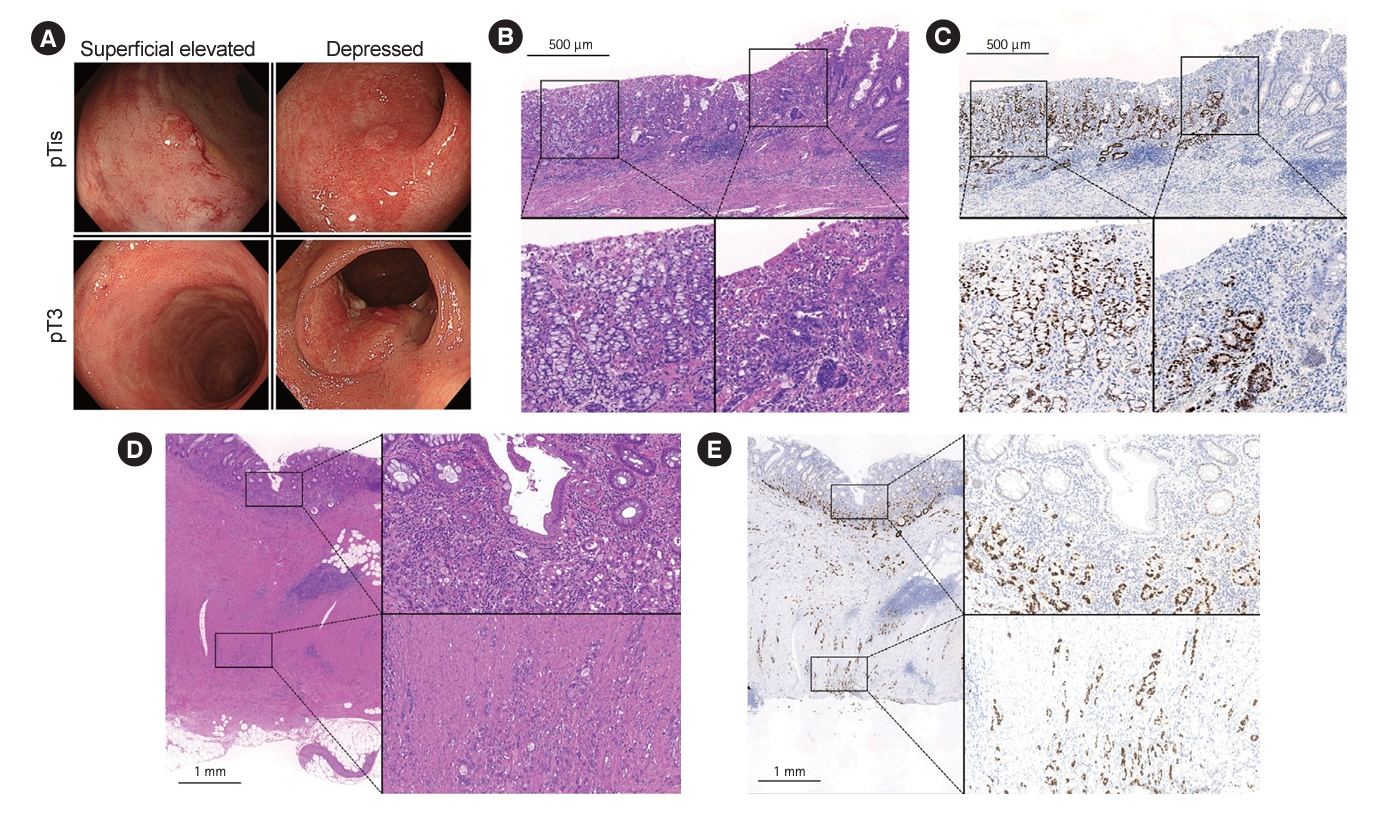

15. Sugimoto S, Naganuma M, Iwao Y, et al. Endoscopic morphologic features of ulcerative colitis-associated dysplasia classified according to the SCENIC consensus statement. Gastrointest Endosc 2017;85:639-646.

16. Mutaguchi M, Naganuma M, Sugimoto S, et al. Difference in the clinical characteristic and prognosis of colitis-associated cancer and sporadic neoplasia in ulcerative colitis patients. Dig Liver Dis 2019;51:1257-1264.

17. Sugimoto S, Iwao Y, Shimoda M, et al. Epithelium replacement contributes to field expansion of squamous epithelium and ulcerative colitis-associated neoplasia. Gastroenterology 2022;162:334-337.

18. Takabayashi K, Sugimoto S, Nanki K, et al. Characteristics of flat-type ulcerative colitis-associated neoplasia on chromoendoscopic imaging with indigo carmine dye spraying. Dig Endosc 2023 Jun 30 [Epub].

https://doi.org/10.1111/den.14628.

19. Schroeder KW, Tremaine WJ, Ilstrup DM. Coated oral 5-aminosalicylic acid therapy for mildly to moderately active ulcerative colitis: a randomized study. N Engl J Med 1987;317:1625-1629.

22. Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum. Japanese classification of colorectal, appendiceal, and anal carcinoma: the 3rd English edition. Tokyo: Kanehara & Co., Ltd., 2019.

23. Kang H, OŌĆÖConnell JB, Maggard MA, Sack J, Ko CY. A 10-year outcomes evaluation of mucinous and signet-ring cell carcinoma of the colon and rectum. Dis Colon Rectum 2005;48:1161-1168.

24. Choi CR, Al Bakir I, Ding NJ, et al. Cumulative burden of inflammation predicts colorectal neoplasia risk in ulcerative colitis: a large single-centre study. Gut 2019;68:414-422.

26. Bak MTJ, Alb├®niz E, East JE, et al. Endoscopic management of patients with high-risk colorectal colitis-associated neoplasia: a Delphi study. Gastrointest Endosc 2023;97:767-779.

28. Kaltenbach T, Holmes I, Nguyen-Vu T, et al. Longitudinal outcomes of the endoscopic resection of nonpolypoid dysplastic lesions in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastrointest Endosc 2023;97:934-940.