|

|

- Search

| Intest Res > Volume 16(4); 2018 > Article |

|

Abstract

The patient-physician relationship has a pivotal impact on the inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) outcomes. However, there are many challenges in the patient-physician relationship; lag time in diagnosis which results in frustration and an anchoring bias against the treating gastroenterologist, the widespread availability of medical information on the internet has resulted in patients having their own ideas of treatment, which may be incongruent from the treating physiciansŌĆÖ goals resulting in patient physician discordance. Because IBD is an incurable disease, the goal of treatment is to sustain remission. To achieve this, patients may have to go through several lines of treatment. The period of receiving stepping up, top down or even accelerated stepping up medications may result in a lot of frustration and anxiety for the patient and may compromise the patient-physician relationship. IBD patients are also prone to psychological distress that further compromises the patient-physician relationship. Despite numerous published data regarding the medical and surgical treatment options available for IBD, there is a lack of data regarding methods to improve the therapeutic patient-physician relationship. In this review article, we aim to encapsulate the challenges faced in the patient-physician relationship and ways to overcome in for an improved outcome in IBD.

The burden of IBD either UC or CD is pronounced and it affects 1.7 million patients in the United States [1], over 3.7 million patients in Europe [2] and its incidence is increasing with approximately 1.5 per 100,000 people in Asia being affected making IBD no longer a Western disease [3]. This disease comprises of symptoms such as chronic diarrhea, weight loss, abdominal pain, malabsorption and gastrointestinal bleeding which can carry potential complications of abscess formation, fistulas and strictures and if uncontrolled can result in significant morbidity [4] hence contributing to significant adverse effects on quality of life [5], emotional and psychosocial well-being and poses a substantial public healthcare burden.

The patient-physician relationship in IBD has gone through tremendous changes over the past decades. During the initial discovery of UC by Sir Samuel Wilks in 1859, the management was focused on the medical and surgical aspects of IBD [6]. The year 1930 heralded the discovery of the role of psychological distress in the pathophysiology of UC [7]. However, despite this discovery, treatment still largely omitted addressing psychological factors in the 20th century. The post-millennial era heralded the discovery of the association between psychological distress and poorer IBD outcomes [8] which were accounted for by the interactions between the brain-gut axis [9]. The advances in the patient-physician relationship are shown in Table 1 [10-16]. Despite all the progress shown in Table 1, the pharmacological advances still far outweigh the advances in communication strategies.

IBD is an incurable chronic disease hence the treatment strategies are directed at controlling the inflammation during the relapses and sustaining remission, which is facilitated by adherence to therapy. The patient-physician relationship has been recognized as the backbone of the continuum of care in IBD management. Patients will not be able to reap the full benefits of their treatment regime as long as non-adherence, psychological distress, under-reporting of symptoms or noncompliance to follow-ups exists. Hence there is a need to amalgamate the advancement of medical therapeutics with robust communication strategies to achieve an optimal outcome. In this review article, we aim to consolidate the challenges faced in the patient-physician relationship while highlighting the importance of effective communication in optimizing IBD outcomes and present guidelines on improving the patient-physician relationship.

Communication in IBD is fraught with many challenges. Each stage of the disease poses unique challenges of its own. The most vulnerable yet pivotal moment of the patient-physician relationship is at the delivery of the diagnosis of IBD. The pitch of this conveyance sets the tone for the rest of the patient-physician relationship. It is important to realize that at this stage, the 2 arduous hurdles are dealing with diagnostic delays and delivering the diagnosis of a chronic, incurable disease that entails periods of flares and remission. Ghosh and Mitchell [5] showed that, 53% of patientsŌĆÖ endured symptoms for 1 year before the actual diagnosis was made meanwhile 20% had to endure symptoms for more than 5 years before their diagnosis. In Korea, the average diagnostic delay was 16 months [17]. This diagnostic delay consequents upon much frustration and anxiety for the patient. Pittet et al. [18] showed that at the onset of the first IBD symptom 65.9% of patients relied on their physician for information while only 36.7% relied on the internet, whereas this number relying on their physicians for information decreased to 31.9% after the diagnosis of IBD and the number of patients relying on the internet increased to 45.4%.

Delivering the diagnosis of IBD is never straightforward. Patients may have the perception that once the diagnosis is made, the next step would be a cure. The initial reaction to the diagnosis can be shock, fear and disbelief and patients often go through the 5 stages of grief [19]. During the initial diagnosis, patients are affronted with numerous questions regarding the aetiology of their disease, its nature [18] and the disease implications given its uncertain trajectory. Communication is the backbone of chronic disease management. The Chronic Care Model enumerates that ŌĆ£optimal chronic illness care is achieved when a prepared, proactive practice team interacts with an informed, activated patient. [20]ŌĆØ

Once the diagnosis has been revealed, educating the patient is of paramount importance. Physicians need to establish the fundamentals of IBD: the chronic and incurable nature which involves periods of flares and remission, at the same time reassured that an arsenal of medication is at hand to facilitate remission while addressing their frustration with diagnostic delays. Understanding the natural history of IBD enables patients to have realistic expectations, improves adherence and provides a platform for them to have an open and honest conversations with their physicians regarding potentially embarrassing symptoms, effects on quality on life, and treatment options. Inadequate understanding about the natural history of IBD may result in disease flares being seen as failure of the physician, which may lead to loss of trust in the physician, noncompliance, seeking of alternative treatment, and in severe cases, results in patients defaulting, which adversely affects outcome. Once the groundwork has been established from the onset of diagnosis, open and honest communication between the physician and the patient is facilitated that is equipped to withstand the onslaught of disease flares while enabling patients to play an active role in their disease management. Table 2 illustrates the barriers in communication in IBD.

One of the dominant factors in predicting the physical health and well-being of the patient is social support. Social support is an interactive process in which emotional, instrumental or financial aid is obtained from network members. Physicians need to ascertain the degree of social support that the patient has as poor social support has been shown to increase psychological distress [8]. Partners should be invited to be a part of the patientsŌĆÖ IBD journey from the start of the IBD diagnosis. One of the objective ways to assess social support can be via the validated social support questionnaire [21] which assesses patientsŌĆÖ network size and satisfaction from perceived available support. Perceived available support is assessed by the following questions, ŌĆ£Whom can you really count on genuinely: (1) to be dependable when you require help; (2) to help you to be more relaxed when you are under pressure; (3) to take care of you despite what is happening to you; (4) to assist you to believe you are more well off when you are generally down-in-the-dumps; (5) to console you when you are very upset; and (6) who accepts you completely, including your strongest and weakest points?ŌĆØ This is a qualitative screening questionnaire, which is designed to pick up patients with poor social support for the institution of remedial measures such as IBD support groups, referring the patient to a social worker and involving the help of an IBD nurse specialist.

Physicians need to recognize how IBD affects patients not only from the medical but also from their personal and sociopsychological viewpoint. Compared to other chronic diseases, IBD patients had more worries about disease complications (84%) and were more prone to depression (62%) and also embarrassment (70%) due to the constellation of IBD symptoms which is made worst during flares [22] with an estimate of 25% to 50% of patients relapsing yearly [23]. Jelsness-J├Ėrgensen et al. [24] showed that patients main concerns are the need for surgery and possibility of having an ostomy bag as patients view this as a major alteration to their body image [24]. Other concerns are the fear of the side effects of medications especially steroids, bowel incontinence, consequences of IBD on their career, fears regarding its impact on relationships, the risk of cancer, societal stigmatization and effects of IBD on fertility [24].

Despite contemporary insight into healthcare related quality of life (HRQoL) impairment in IBD, conversations about HRQoL do not happen as often as they should. In a recent survey conducted by Ghosh and Mitchell [5] in Europe, approximately half of the gastroenterologists do not enquire about patients HRQoL. In fact, approximately 50% of the emotional problems are not reported in patients with IBD [25]. Physicians also tend to underestimate the repercussions that IBD has on patientsŌĆÖ HRQoL [26] and tend to minimize patients symptoms. Rubin et al. [22] showed that 78% of IBD patients reported that IBD impacted their HRQoL and 55% of the patients who were affected did not have a conversation with their physician about the effects of IBD on their HRQoL. This adversely affects the outcome of IBD, as psychological distress is associated with increased disease activity and relapse [27].

Effective eliciting of patients concerns has many facets. An effective tool is the rating form of IBD patient concerns (RFIPC) [28], which is a psychometric tool that provides an accurate characterization of patients IBD related worries and concerns. The RFIPC consist of 25 item questions which begins with the question, ŌĆ£Because of your condition, how concerned are you withŌĆ”ŌĆØ Patients rated their concerns on a 10-cm visual analogue scale and these responses were then converted to scores which range from 0 to 100 and offers physiciansŌĆÖ insight into the issues that concern patients the most with regards to IBD as illustrated in Table 3. The accurate identification of worries and concerns enables the physician to implement specific interventions that improves patientsŌĆÖ HRQoL, which can improve the outcome of disease.

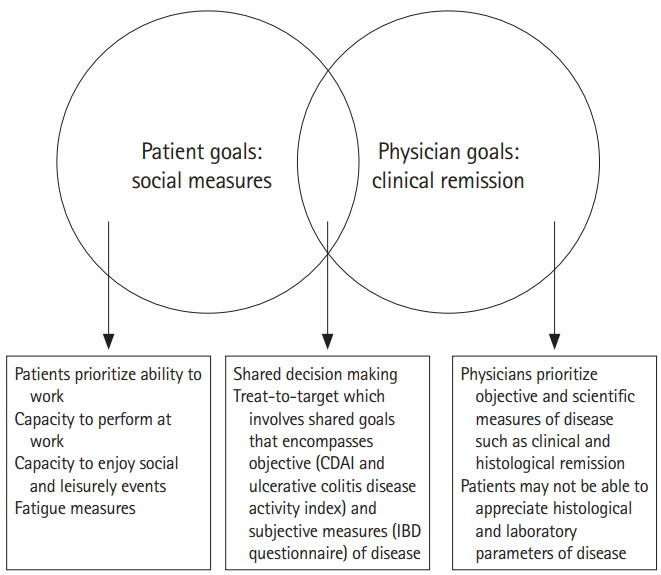

The dynamics of patient-physician relationship has undergone tremendous change from the traditional pre-millennial landscape where patients were accustomed to ŌĆ£follow doctorsŌĆÖ ordersŌĆØ and where partnership and joint decision-making was not widely practiced. Patients and physicians engender 2 sets of ideologically different perceptions about the characteristics of the disease and treatment. Vaucher et al. [29] showed that physicians and patients had differing views when it came to outcome of treatment: Physicians prioritized objective and scientific measures of remission (histological remission), whereas patients perceived remission as clinical remission with tangible improvement in quality of life as well as social outcomes. Fig. 1 illustrates the amalgamation of patients and physiciansŌĆÖ goal of IBD treatment.

Rubin et al. [30] demonstrated that although physiciansŌĆÖ treatment approaches were up-to-date with the current guidelines, the stigma regarding the adverse effects of treatment resulted in a gap between patientsŌĆÖ wishes and their actual prescribed medications. In an interventional study conducted by Siegel [15] about shared decision making, one-third of patients did not understand the advantages, dangers and potential risks of their treatment options and as a result changed physicians because there was discordance between patients wishes and preferences and physicians treatment choices and goals. In a recent survey conducted by Baars et al. [31], 82% of patients wanted to participate in the process of decision-making.

The change of landscape highlights that patients want a paradigm shift from being a passive health consumer to an active health partner. Physicians need to assimilate patients into the process of treatment decision-making by empowering them to make evidence-based informed decision. This is achieved by delivering scientific evidence in patient friendly terms and carrying out educational empowerment to increase health literacy.

In order for patients to play a role as health partners, patientsŌĆÖ need to understand the fine balance between the risks of treatment versus the detriment of under treatment and appreciate ultimately that the benefit of remission far outweighs the risks. This is approached in a stepwise manner; the goal of rapid disease remission that is achieved via corticosteroids but limited to short term use and the strategies for long-term remission, which are immunomodulators and or biologics. One of the main concerns of biologic therapy is the risk of infection, but this risk can be reduced with thorough history taking and recommended pre-screening strategies before initiation of therapy and counselling on recognition of early signs of infection. IBD is predominantly diagnosed in late puberty and early adulthood, the median age of diagnosis 29.5 years and the patients come from a variety of educational backgrounds [32]. Hence, a method of explanation that will cater to all backgrounds that is comprehensive yet easy to understand such as the one illustrated in Table 4 will enable patients to better appreciate the risk and benefits of each treatment option.

Open and honest discussion about the adverse effects and risk of medication facilitates the next step of the process of coming to a treatment decision via shared-decision-making. In this framework, physicians have the duty of educating patients on the treatment options and recommending treatment to patients while taking into account their preferences, treatment goals, inclinations and risk profile but the process of deciding on the treatment strategy is shared. This facilitates ŌĆ£evidence-based patient choice.ŌĆØ This has been shown to improve patient adherence, self-management, reduce healthcare cost [15] and increase patient satisfaction with the healthcare they received.

Once a joint decision on treatment strategy has been reached, the treat-to-target approach is a useful tool in achieving histoFig. 1. Amalgamating patients and physicians goals of treatment. logical remission via rapid optimization of therapy. Treat-to-target strategy was developed via a negotiation strategy modified from a highly successful business negotiation model [33]. The first and most important step is to identify and understand patientsŌĆÖ fears about treatment and address them. Physicians then need to correct any misinformation that patients have about their fears of treatment.

The second step is explaining the importance of objective parameters in monitoring the disease activity, which is not based on symptomatic assessment alone but involves other objective parameters (CRP, fecal calprotectin, endoscopic and histological assessments) and the mechanism by which the proposed treatment will potentially improve these parameters. Physicians and patients then set joint treatment goals. Once a treatment goal has been agreed upon, the third step will be setting a time frame for this goal to be achieved. Physicians and patients then agree upon a set time frame to achieve these treatment goals and work together to explore different treatment options if there is no measurable change in the disease status [16,34]. This strengthens the patient-physician partnership as patients understand the goals of their treatment and become partners with their physicians in seeing these goals achieved.

To date, the assessment measure of IBD include CDAI and ulcerative colitis disease activity index (UCDAI). Although clinically accurate, these scores omit an important aspect of IBD: the effects of IBD on HRQoL. Loftus et al. [35] showed the importance of assessment of patient-reported-outcomes in the evaluation of the efficacy of the treatment regime. This can be assessed via the IBD questionnaire (IBDQ) that assesses 4 broad parameters; gut associated symptoms (diarrhea, abdominal pain), systemic effects of IBD (lethargy, insomnia), functional assessment (capacity to work, ability to enjoy leisurely activities) and emotional condition (irritability, anger) [36]. Scores range from 32 to 224 with higher scores indicating better HRQoL A pretreatment assessment should be performed, and improvement of more than 16 post-treatment scores indicates good improvement and a score of greater than 170 corresponds with remission. The evaluation of patient-reported-outcomes assesses parameters that are of importance to patients in terms of treatment goals and creates a more holistic approach in the care of IBD.

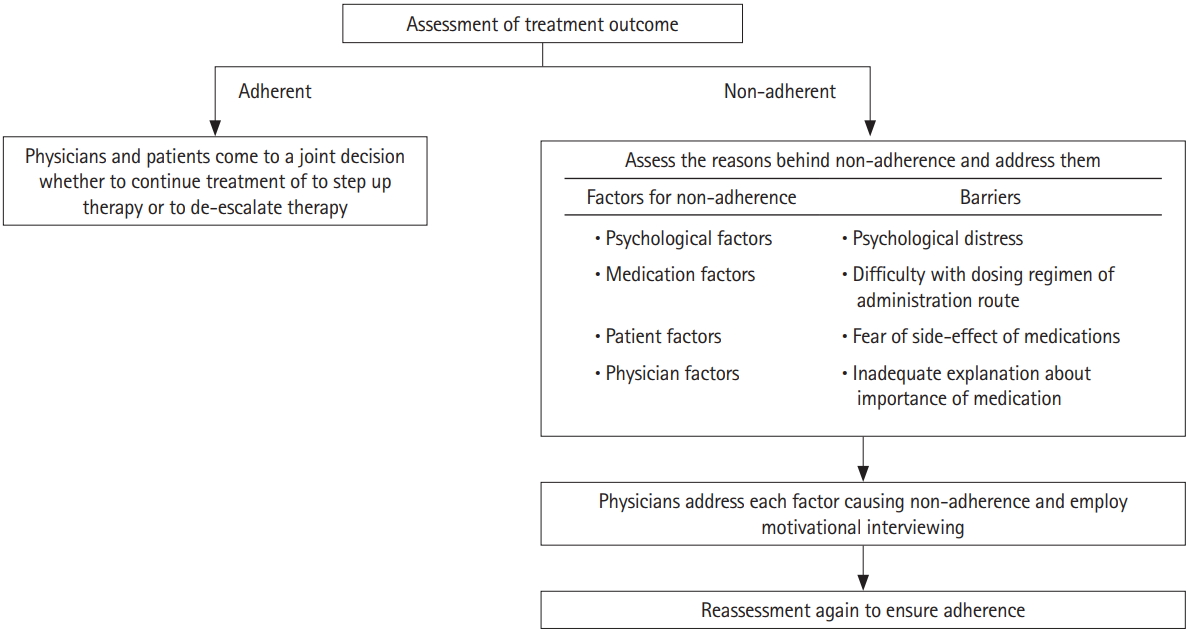

One of the major culprits of non-adherence is ineffective communication, the repercussions of which is poor understanding of the nature of IBD resulting in unawareness of the severity as well as the potential life threatening consequences of the disease [37].

This gives rise to doubts regarding the necessity [37] and effectiveness of medications [37] this compounded by unaddressed concerns regarding the side effects of medication [38] leads to noncompliance to therapy and follow ups. Non-adherence is usually a covert problem: concealed by the patient and not adequately picked up by physicians. One of the major challenges in the management of IBD is non-adherence with studies reporting that an average of 30% to 45% of patients were not adherent to their oral medication (defined as taking less than 80% of their medication) [39].

A systematic review conducted by Higgins et al. [37] showed that mesalazine non-adherence substantially elevated the danger of UC relapse. About 68% IBD patients whose disease were in remission experienced a recurrence of symptoms due to non-adherence to therapy [40]. Despite advances in therapeutic options available, patients will not receive full benefits without adherence to medical treatment. The most important step in improving non-adherence is understanding the psychology of non-adherence which can be divided into physician factors: (1) inadequate information about medications [38]; (2) patient-physician discordance [38]; and (3) lack of trust in the treating physician [38], medication factors; inconveniences with oral and topical therapy with patients citing hassle of topical therapy especially at work as a contributing factor to non-adherence [25] and finally and patient factors; non-adherence was associated with poorer quality of life [41], psychiatric diagnosis [42], psychological distress [32] as well as depression [16] and anxiety [41].

One of the methods to improve non-adherence is motivational interviewing. Motivational interviewing is a communication tool in IBD, which is patient-centred and designed to address and overcome the patientsŌĆÖ attitude of indifference towards change [43]. It was initially established in the context of recovery from substance abuse and replaced the traditional approach of addiction interventions, which utilised heavy confrontation of the patientsŌĆÖ denial and resistance to rehabilitation [44]. This involves 4 core principles: The first is engaging the patient. The second principle is focusing to redirect patients attention to the need for change that comes with the diagnosis of IBD which requires regular medicine taking and follow up appointments and endoscopies. The 3rd principle is evoking which is eliciting their personal lifetime goals and hopes for disease remission and then eliciting the patientsŌĆÖ motivation for disease control. The final step is planning which encompasses consolidating the commitment towards disease control and formulating a plan of action to achieve disease control via adherence to medication and follow ups and seeking prompt medical care when symptoms of flares occur [45]. This method of communication has shown to improve adherence to treatment and follow up visits and increase patient satisfaction.

Depression is a prevalent problem in IBD. However, depression in patients with IBD has often been under recognized and undertreated. A recent systematic review showed that depression was as high as 21.2% in patients with IBD compared to 12.4% of healthy subjects and this number rose to 34% in patients with active IBD [46]. Depression adversely affects the outcomes in IBD as it has been shown to increase non-adherence and results in decreased HRQoL [47], impacts ability of patients to self-manage and can results in poorer clinical outcomes due to the activation of the brain-gut axis. Evidence points to the fact that inflammation is increased in depressed individuals compared to healthy subjects with specific increase in serum levels of interleukin (IL)-1, -6, -12 and tumor necrosis factor-╬▒ and possible attenuations in IL-12 pathways [48]. A longitudinal study done by Mikocka-Walus et al. [49] observed that depression was linked to physician-reported clinical relapse and depressed patients have a shorter time to clinical recurrence.

Patients should be screened for depression using psychological instruments such as Beck Depression Inventory and Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale to evaluate their mental health status. Depression commonly presents with low mood, anhedonia, feelings of guilt, worthlessness or hopelessness and difficulties in concentrating, reduced energy levels and sleeping disturbance [42]. When these symptoms last beyond 2 weeks and begin to interfere significantly with activities of daily living, they are considered clinically significant. Once depression has been identified, mental health interventions which encompass cognitive-behavioral therapy [50] and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [51] have been shown to be beneficial. Multidisciplinary care and prompt referral to psychiatry can greatly benefit the alleviation of depression. A summary of effective communication strategies that include a stepwise approach from the time of diagnosis to the therapeutic management is shown in Table 5 and Fig. 2.

Patient-physician communication in the Asian context presents more challenges due to the cultural as well as the epidemiological nuances in Asia. Firstly, there is a diagnostic challenge is distinguishing IBD from gastro-intestinal tuberculosis (giTB), which has a high prevalence in Asia, and there is a high propensity of misdiagnosis of either condition [52]. As such, patients in Asia may have to endure an even longer lag time of diagnosis and may be even misdiagnosed with giTB and commenced on treatment prior to establishment of the correct diagnosis. This creates a deeper wedge between the patient-physician relationship requiring physicians to explain the burden of infectious disease in Asia and why it has to be strictly excluded before the diagnosis of IBD is made as commencement of definitive therapy for IBD increases the susceptibility to infections and with pre-existing TB, this may result in a fulminant flare which may be lethal.

Secondly, there is a preponderance of widespread use of traditional and alternative medications in Asia. Patients may choose to seek alternative and traditional medication altogether or take it concurrently with their conventional IBD medication. Dissatisfaction with the patient-physician relationship, adverse effects of conventional medication and psychological distress influence seeking alternative and traditional medication behavior [53]. Alternative and traditional medicine do not have robust data supporting its efficacy and may cause potential harm instead. It is estimated that up to 75% of patients consuming alternative and traditional medication do not disclose this to their treating physicians [54]. The interaction between alternative and traditional medication and conventional IBD medication could render IBD treatment less effective, worst still it could lead to consequences such as drug induced liver injury and drug interaction. Physicians in Asia need to be aware of the prevalence of alternative medication seeking behavior and be mindful of factors that promote this as failure to recognize this may cause patients to be non-adherent to medication and default follow-ups which leads to compromised care.

Thirdly, there are economic limitations when it comes to treatment options in Asia, while anti-TNF is the mainstay of treatment for patients with moderate to severe UC and CD as well as fistulizing CD, its usage is limited by its cost in the Asian context. This may results in poorer outcomes in Asia, which leads to a vicious cycle of patients being dissatisfied with care hence increasing the risk of non-adherence, defaulting and alternative medicine seeking behavior. Fourthly, there is a stigma associated with surgical resection for IBD in Asia, leading to a lower rate of surgical resection, and possibly suboptimal outcomes [3]. Physicians need to recognize this and address the specific fear of surgery, which may be related to fear of loosing a body part, or even boil down to religious reasons. Next-of-kin should be invited to be part of the consultation as they have a great influence in the Asian society on patientsŌĆÖ health decision. Both patients and next-of-kin need to be diligently educated regarding the natural history of IBD, the complications and the need for conventional treatment and the importance of surgery in selected cases.

The other challenge that exists is the intrinsic Asia Pacific patient-physician model of communication differs from that of the West due the fact that the concept of patient autonomy is still reaching maturity due to the hierarchal culture, which results in a patriarchal view of medicine [55]. As such communication tends to be physician focused where the physicianŌĆÖs agenda dominates the consultation. PhysicianŌĆÖs communication tends to be task based and more focused on the medical aspect of communication. PatientsŌĆÖ communication also tends towards agreement with the physician and they do not routinely voice out their concerns and queries to their physicians, as the Asian culture tends to not be as forthright and more subdued.

Another challenge faced by Asian physicians is the multicultural and multi-ethnic diversity in Asia. Communication challenges arise from language barrier, due to the diverse dialects in Asia, inadequate knowledge of the treating physician on the cultural differences of different ethnicities and its influence on their medical beliefs and attitudes. The stigma associated with depression may also result in psychological distress being missed in Asian patients. Because of the societal stigmatization, patients start to see themselves as undeserving of care, responsible for their illness and unable to recover which further worsens their depression. Physicians need to be aware of the cultural nuances in the Asian context and tailor communication to incorporate patient participation as highlighted in Table 6. With increasing availability of information and increasing awareness on the importance of physician-patient partnerships, we believe that this paradigm shift is foreseeable in the future.

The patient-physician relationship is the cornerstone of care in the management of IBD. There is a need for improved communication strategies to enhance the outcome of IBD. The recognition of the brain-gut axis highlights the importance of recognizing psychological distress and HRQOL impairment in IBD via improved patient-physician communication. There has been a paradigm shift in the recent years in trend of the patient-physician relationship. There is an evolution away from the traditional communication model held in the premillennial era where patients had a much lesser involvement in the treatment decision making process also were expected to follow doctors orders. The shift in trend is attributed to the increase in education levels as well as the widespread availability of medical information. The widespread of availability of information has become a 2-edged sword with patients having their own ideas about treatment decision and outcome wanting more autonomy and involvement in their treatment which can lead to physician-patient discordance. Physicians need to incorporate assessment of HRQoL via IBDQ into the standard assessment of severity of IBD via CDAI and UCDAI for a holistic approach to care. The bio-psychosocial model of communication allows physicians to better understand patients and gain greater insight into matters pertaining to their quality of life and allows for earlier detection of psychological distress. With improved physician-patient relationship, an improvement in adherence, quality of life and finally clinical outcomes among patients with IBD will be achieved.

Communication in the Asian context has its own set of challenges that are unique to the epidemiological, economic and cultural nuances in Asia. Physicians need to be mindful of the possible increase in lag time to diagnosis, the use of traditional and alternative medicines, the stigma associated with surgery and the economic implications and its restrictions on availability of treatment. This may require physicians to allocate more time for the IBD patients as well as involve next-of-kin in their care, as patients families play a huge role in determining their health behavior. With increasing awareness on the importance of the patient-physician relationship in the outcome of IBD there is an imperative towards changing communication trends towards partnership style with an egalitarian contribution from both patients and physicians for improved IBD outcomes.

NOTES

Table┬Ā1.

Landmarks of Advances in the Patient-Physician Relationship in IBD

| Era and communication style | Year | Landmark | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-millennial | |||

| Traditional patient-physician relationship where patients were expected to ŌĆ£follow doctorŌĆÖs ordersŌĆØ | 1930s | Murray first describes the association between psychological distress and UC and postulated that patients with UC may have emotional disturbance since childhood to account for the disease. [10] | |

| Doctors were the main source of patientsŌĆÖ information | 1930s | UC was postulated to be a psychosomatic disorder by Alexander where he theorized that psychic alterations influenced the behavior of the gut towards 3 tendencies: the gastric type with a wide range of gastric symptoms, the colitis type with symptoms of diarrhea and the constipation type. [11] | |

| Doctors were the main decision-makers in determining treatment | 1930s | Sullivan and Chandler demonstrates an improvement in the outcome of UC with psychotherapy when numerous other conventional forms of treatment had failed. This was however met with great skepticism. [7] | |

| Limited treatment options for IBD | 1957 | Banks et al. made an important observation that emotional stress often precedes UC flares. [12] | |

| Definition of remission was clinical remission | 1984 | Murray publishes a review article on psychological factors in UC and notes that physicians who offer their patients reassurance cause their patients to feel better overall, recognizing the importance of the patient-physician relationship. [13] | |

| Post-millennial | |||

| Concept of patient autonomy introduced | 2002 | Numerous studies in chronic illness showed that patients who were actively involved in the decision-making process and had a strong patient-physician relationship had better adherence to treatment. Goldring et al. conducted a similar study in IBD, which showed that joint decision-making and a positive patient-physician relationship improved adherence and outcome of IBD. [14] | |

| Widespread availability of medical information especially from the internet | 2012 | Siegel introduce shared-decision-making in IBD to present to patients the treatment options as well as the step-up versus top-down approach to come to a conjoint and informed decision regarding therapy, which can improve adherence and outcome of IBD. [15] | |

| Shared-decision-making takes where patients and doctors reach an agreement on the treatment decision | 2013 | Bonaz and Bernstein published a hallmark paper on the brain-gut axis interactions and highlights a very important aspect on how psychological distress can adversely affect IBD. This implication cements the importance of the patient-physician relationship and the role of the physician in recognizing psychological distress, defective coping strategies and depression and instituting the appropriate interventions. [9] | |

| Vast arsenal of treatment options for IBD | 2016 | Bossuyt and Vermeire introduces the concept of treat-to-target strategy to enhance the patient-physician partnership to improve outcomes. [16] | |

Table┬Ā2.

Barriers in Communication in IBD

Table┬Ā3.

Characterization of Worries and Concerns of IBD Patients

Table┬Ā4.

Counselling Tools for Long-Term Treatment Options in IBD

| Treatment | Benefits | Risk |

|---|---|---|

| Immunomodulators | ŌłÖ Maintain remissiona | Skin cancerb |

|

|

|

| Risk of infectionb | ||

|

||

| Risk of low white cell countsb | ||

|

||

| Risk of liver enzyme derangementb | ||

|

||

| Biologics | ŌłÖ Maintain remissiona | Lymphomab |

|

|

|

| Risk of infectionb | ||

|

||

| Risk of loosing its efficacyb | ||

|

Table┬Ā5.

Stepwise Approach in Improving the Patient-Physician Communication from Diagnosis to Therapeutic Outcome Assessment

Table┬Ā6.

Challenges Unique to the Asian Landscape of Communication

REFERENCES

1. Kappelman MD, Moore KR, Allen JK, Cook SF. Recent trends in the prevalence of CrohnŌĆÖs disease and ulcerative colitis in a commercially insured US population. Dig Dis Sci 2013;58:519-525.

2. Burisch J, Jess T, Martinato M, Lakatos PL; ECCO-EpiCom. The burden of inflammatory bowel disease in Europe. J Crohns Colitis 2013;7:322-337.

3. Ng SC. Emerging trends of inflammatory bowel disease in Asia. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2016;12:193-196.

4. Allez M, Modigliani R. Clinical features of inflammatory bowel disease. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2000;16:329-336.

5. Ghosh S, Mitchell R. Impact of inflammatory bowel disease on quality of life: results of the European Federation of CrohnŌĆÖs and Ulcerative Colitis Associations (EFCCA) patient survey. J Crohns Colitis 2007;1:10-20.

6. Wilks S. Morbid appearances in the intestine of Miss Bankes. Med Times Gaz 1859;2:264-265.

7. Sullivan AJ, Chandler CA. Ulcerative colitis of psychogenic origin: a report of six cases. Yale J Biol Med 1932;4:779-796.

8. Sewitch MJ, Abrahamowicz M, Bitton A, et al. Psychological distress, social support, and disease activity in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2001;96:1470-1479.

9. Bonaz BL, Bernstein CN. Brain-gut interactions in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 2013;144:36-49.

10. Murray C. Psychologenic factors in the etiology of ulcerative colitis and bloody diarrhea. Am J Med Sci 1930;180:239-248.

11. Alexander F. The influence of psychological factors upon gastrointestinal disturbances: a symposium. I. General principles, objectives and preliminary results. Psychoanal Q 1934;3:501-539.

12. Banks BM, Korelitz BI, Zetzel L. The course of nonspecific ulcerative colitis: review of twenty yearsŌĆÖ experience and late results. Gastroenterology 1957;32:983-1012.

14. Goldring AB, Taylor SE, Kemeny ME, Anton PA. Impact of health beliefs, quality of life, and the physician-patient relationship on the treatment intentions of inflammatory bowel disease patients. Health Psychol 2002;21:219-228.

15. Siegel CA. Shared decision making in inflammatory bowel disease: helping patients understand the tradeoffs between treatment options. Gut 2012;61:459-465.

16. Bossuyt P, Vermeire S. Treat to target in inflammatory bowel disease. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol 2016;14:61-72.

17. Moon CM, Jung SA, Kim SE, et al. Clinical factors and disease course related to diagnostic delay in Korean CrohnŌĆÖs disease patients: results from the CONNECT study. PLoS One 2015;10:e0144390. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0144390.

18. Pittet V, Vaucher C, Maillard MH, et al. Information needs and concerns of patients with inflammatory bowel disease: what can we learn from participants in a bilingual clinical cohort? PLoS One 2016;11:e0150620. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150620.

19. Husain A, Triadafilopoulos G. Communicating with patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2004;10:444-450.

20. Fiandt K. The Chronic Care Model: description and application for practice. Top Adv Pract Nurs 2006;6(4.

21. Sarason IG, Sarason BR, Shearin EN, Pierce GR. A brief measure of social support: practical and theoretical implications. J Soc Pers Relat 1987;4:497-510.

22. Rubin DT, Dubinsky MC, Panaccione R, et al. The impact of ulcerative colitis on patientsŌĆÖ lives compared to other chronic diseases: a patient survey. Dig Dis Sci 2010;55:1044-1052.

23. Riley SA, Mani V, Goodman MJ, Lucas S. Why do patients with ulcerative colitis relapse? Gut 1990;31:179-183.

24. Jelsness-J├Ėrgensen LP, Moum B, Bernklev T. Worries and concerns among inflammatory bowel disease patients followed prospectively over one year. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2011;2011:492034doi: 10.1155/2011/492034.

25. DŌĆÖInc├Ā R, Bertomoro P, Mazzocco K, Vettorato MG, Rumiati R, Sturniolo GC. Risk factors for non-adherence to medication in inflammatory bowel disease patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2008;27:166-172.

26. Schreiber S, Pan├®s J, Louis E, Holley D, Buch M, Paridaens K. National differences in ulcerative colitis experience and management among patients from five European countries and Canada: an online survey. J Crohns Colitis 2013;7:497-509.

27. Porcelli P, Leoci C, Guerra V. A prospective study of the relationship between disease activity and psychologic distress in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol 1996;31:792-796.

28. Drossman DA, Leserman J, Li ZM, Mitchell CM, Zagami EA, Patrick DL. The rating form of IBD patient concerns: a new measure of health status. Psychosom Med 1991;53:701-712.

29. Vaucher C, Maillard MH, Froehlich F, Burnand B, Michetti P, Pittet V. Patients and gastroenterologistsŌĆÖ perceptions of treatments for inflammatory bowel diseases: do their perspectives match? Scand J Gastroenterol 2016;51:1056-1061.

30. Rubin DT, Dubinsky MC, Martino S, Hewett KA, Pan├®s J. communication between physicians and patients with ulcerative colitis: reflections and insights from a qualitative study of in-office patient-physician visits. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2017;23:494-501.

31. Baars JE, Markus T, Kuipers EJ, van der Woude CJ. PatientsŌĆÖ preferences regarding shared decision-making in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease: results from a patient-empowerment study. Digestion 2010;81:113-119.

32. Loftus EV Jr, Silverstein MD, Sandborn WJ, Tremaine WJ, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR. CrohnŌĆÖs disease in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1940-1993: incidence, prevalence, and survival. Gastroenterology 1998;114:1161-1168.

33. Fisher R, Ury W, Patton B. Getting to yes: negotiating agreement without giving in. New York: Penguin, 2011.

34. Bouguen G, Levesque BG, Feagan BG, et al. Treat to target: a proposed new paradigm for the management of CrohnŌĆÖs disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;13:1042-1050.e2.

35. Loftus EV, Feagan BG, Colombel JF, et al. Effects of adalimumab maintenance therapy on health-related quality of life of patients with CrohnŌĆÖs disease: patient-reported outcomes of the CHARM trial. Am J Gastroenterol 2008;103:3132-3141.

36. Irvine EJ, Feagan B, Rochon J, et al. Quality of life: a valid and reliable measure of therapeutic efficacy in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Canadian CrohnŌĆÖs Relapse Prevention Trial Study Group. Gastroenterology 1994;106:287-296.

37. Higgins PD, Rubin DT, Kaulback K, Schoenfield PS, Kane SV. Systematic review: impact of non-adherence to 5-aminosalicylic acid products on the frequency and cost of ulcerative colitis flares. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2009;29:247-257.

38. L├│pez San Rom├Īn A, Bermejo F, Carrera E, P├®rez-Abad M, Boixeda D. Adherence to treatment in inflammatory bowel disease. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2005;97:249-257.

39. Jackson CA, Clatworthy J, Robinson A, Horne R. Factors associated with non-adherence to oral medication for inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol 2010;105:525-539.

40. Kane S, Huo D, Aikens J, Hanauer S. Medication nonadherence and the outcomes of patients with quiescent ulcerative colitis. Am J Med 2003;114:39-43.

41. Shale MJ, Riley SA. Studies of compliance with delayed-release mesalazine therapy in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2003;18:191-198.

42. Nigro G, Angelini G, Grosso SB, Caula G, Sategna-Guidetti C. Psychiatric predictors of noncompliance in inflammatory bowel disease: psychiatry and compliance. J Clin Gastroenterol 2001;32:66-68.

43. Rotgers F. Motivational interviewing: preparing people to change addictive behavior. J Stud Alcohol 1993;54:507.

44. Martins RK, McNeil DW. Review of motivational interviewing in promoting health behaviors. Clin Psychol Rev 2009;29:283-293.

45. Mocciaro F, Di Mitri R, Russo G, Leone S, Quercia V. Motivational interviewing in inflammatory bowel disease patients: a useful tool for outpatient counselling. Dig Liver Dis 2014;46:893-897.

46. Mikocka-Walus A, Knowles SR, Keefer L, Graff L. Controversies revisited: a systematic review of the comorbidity of depression and anxiety with inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2016;22:752-762.

47. L├│pez-Sanrom├Īn A, Bermejo F. Review article: how to control and improve adherence to therapy in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2006;24 Suppl 3:45-49.

48. Martin-Subero M, Anderson G, Kanchanatawan B, Berk M, Maes M. Comorbidity between depression and inflammatory bowel disease explained by immune-inflammatory, oxidative, and nitrosative stress; tryptophan catabolite; and gut-brain pathways. CNS Spectr 2016;21:184-198.

49. Mikocka-Walus A, Pittet V, Rossel JB, von K├żnel R; Swiss IBD Cohort Study Group. Symptoms of depression and anxiety are independently associated with clinical recurrence of inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;14:829-835.e1.

50. Mikocka-Walus A, Bampton P, Hetzel D, Hughes P, Esterman A, Andrews JM. Cognitive-behavioural therapy for inflammatory bowel disease: 24-month data from a randomised controlled trial. Int J Behav Med 2017;24:127-135.

51. Yanartas O, Kani HT, Bicakci E, et al. The effects of psychiatric treatment on depression, anxiety, quality of life, and sexual dysfunction in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2016;12:673-683.

52. Li Y, Qian JM. The challenge of inflammatory bowel disease diagnosis in Asia. Inflamm Intest Dis 2017;1:159-164.

53. Mountifield R, Andrews JM, Mikocka-Walus A, Bampton P. Doctor communication quality and FriendsŌĆÖ attitudes influence complementary medicine use in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol 2015;21:3663-3670.

- TOOLS